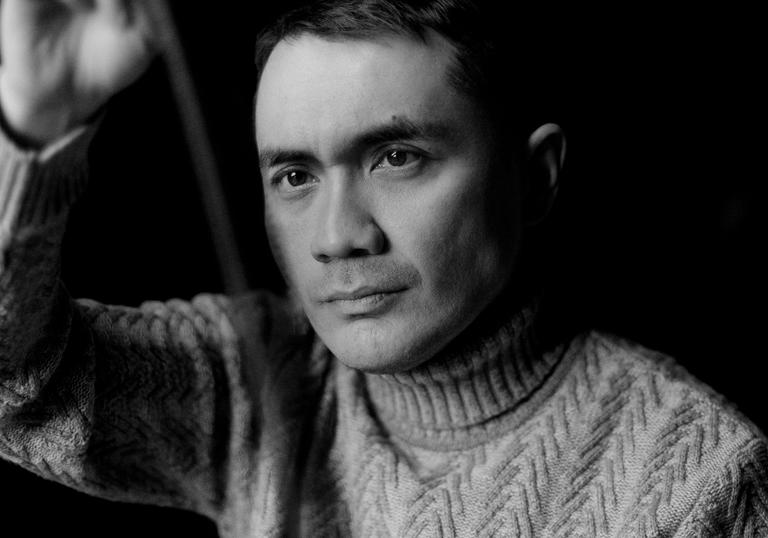

The brilliant crime drama, set in rural Kazakhstan, follows an unprincipled detective who is compelled to expose deeply engrained corruption.

Olya Sova: I am a fan of your films. I am fascinated by their simplicity, their visuals and their deep emotional resonance. In some interviews you call A Dark, Dark Man a film noir. But there is also poetic realism, humour absurdity in the film. How would you define its genre? Is it a Kazakh noir?

Adilkhan Yerzhanov: If you judge it superficially (or, conversely, go in too deep), then it probably is a film noir. I think there is noir in some of its specific elements. We can say that noir is a genre in France, there’s noir in Hong Kong. There is to some extent Russian noir. But, I don’t know, this genre – Kazakh noir – doesn’t really exist. But I’ve always dreamed of it, and I’d love the genre steppe-noir to emerge in this country, so we can become the exporters of this particular genre.

OS: Speaking of Hollywood noir – it emerged from a backdrop of depression and war, after WWI and during WWII. What period do you think Kazakhstan is living through right now?

AY: Before the pandemic, I thought we were living through a kind of crisis, perhaps approaching a crossroads. But during the pandemic I realized that it was a common turning point for everyone, and this turning point, in a strange way, united all countries. And I realized that before the pandemic, before coronavirus, we were all living with pretty minor problems.

But now it’s clear that everyone – the whole world – has become the COVID generation. In Fight Club the characters say that they are the middle children of history, because they have neither their own world war, nor their own Great Depression, and they are deprived of everything, there is not even one big problem. It seems to me that our generation has received its own world war - this pandemic.