In the opening scene of the 1932 film The Lor Girl, the first Persian-language ‘talkie’, a young woman rushes around the perimeter of an open-air cabaret serving tea and snacks to a crowd of cackling, boisterous bandits. Dutiful in demeanour, with dark eyes and long braids, the girl is suddenly interrupted when a group of men begin shouting at her to come and serve them. Struck by their aggression, the girl shouts back in defiance, ‘My name is Golnar!’ – and in this moment, cinematic history is made. Played by the newly discovered Iranian actress Roohangiz Saminejad (1916–1997: she was just 18 at the time), Golnar and her dulcimer-pitched voice reverberated in cinemas across the country, catalysing a new era of Iranian cinema that flagrantly flouted cultural norms.

Golnar’s centrality to the film’s narrative and her bold behaviour made visible a set of intersecting questions about the role of women in a society undergoing rapid modernisation and dynamic cultural change under Reza Shah’s reformist regime in the years 1925 to 1941. Unlike Golnar, Iranian women in 1932 were still unable to speak in public spaces or be seen in public unveiled, creating a yawning gap between reality and cultural production. And yet, in spite of the film’s scandalous premise and shocking representation of women, The Lor Girl was a commercial success – a contradiction that points to the ways in which cinema (and popular culture at large) provided a social space for debate and reflection in pre-revolutionary Iran, even as changes in cultural and political life unfolded at differing speeds. As the Iranian state’s unresolved position on the rights of women grew increasingly fraught across the Pahlavi era (1925–79), Iranian women’s lives bore the brunt of the many conflicts and contradictions playing out in the wider social sphere. These tensions are evident in the story of the actress Saminejad herself, who, in spite of her distinguished filmography and popular success, faced intersecting forms of social exclusion and sexual harassment that lasted until her death in April 1997. An early icon of global cinema, Saminejad and her work remain almost unknown to contemporary Iranians and film scholars alike, even though her contributions to the art form expanded opportunities for other women in the industry.

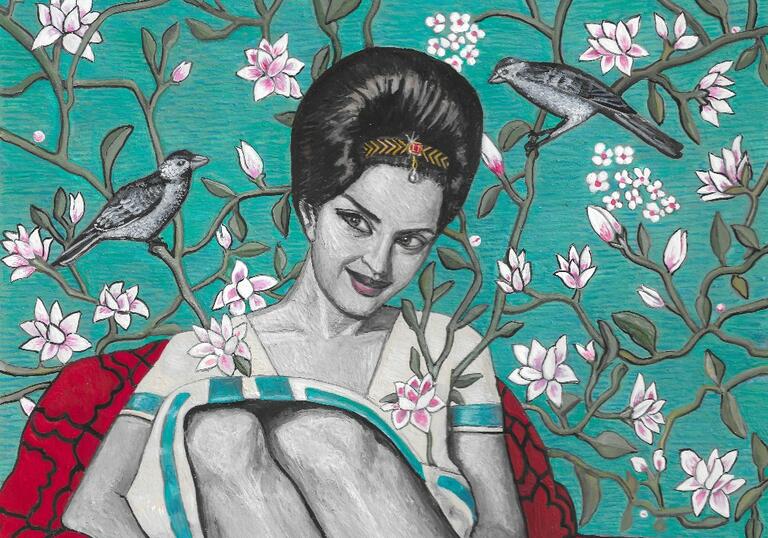

It's no wonder then that Saminejad’s portrait forms the opening of artist Soheila Sokhanvari’s powerful tribute to the women – known and unknown – who shaped Iran’s twentieth-century cultural history but whose stories have been lost, ignored or devalued in the decades since the 1979 revolution. Painted in an energetic monochrome symphony at the scale of a Persian miniature, Saminejad’s presence is made tangible by the rippling lines of her glossy black hair and the field of tiny dots that pressurise the space around her, breathing energy and life into the archival photograph on which this painting is based. Captured in a confident stare, her gaze is commensurate with her film star status. Saminejad is not only the centre of her own image but the catalyst for Sokhanvari’s rebellious archive –a fragmented history of Iranian women artists working and speaking across generations and circumstance. Gathered together in a cadre of 28 individual portraits, Sokhanvari transforms the Curve gallery into a glittering memorial hall as a way of underscoring the historical significance of these women’s lives and livelihoods; each enacts Golnar’s shout for visibility and respect in a society biased towards their silence and erasure. Seen in this way, Sokhanvari offers up not only a site of sacred preservation (a place to house traces of the past and grant them dignity) but an invitation to activate our knowledge-making of Iranian women’s histories into the future.

Sokhanvari’s affirmation of these women’s lives and the tensions that they bear is articulated in her creation of a hybrid portrait genre grounded in the legacies of Persian miniature painting and the European martyr portrait. In an act of feminist defiance, Sokhanvari seizes two representational traditions to construct a new set of visual conditions supportive of these women’s experiences within both Western and Eastern patriarchal systems. A courtly, aristocratic form central to the history of Iranian visual culture across eight centuries, Persian miniature paintings' conventions and traditions find bold expression in Sokhanvari’s modern interpretation: the employment of traditional pigments and processes of preparation, adherence to a ‘miniature’ scale (sometimes the images are just a few square centimetres), the use of detailed patterning, and an emphasis on the centrality of the human figure and its surroundings. Meticulously painted and ornamented despite their small scale, Sokhanvari’s portraits not only affirm these women’s Iranian heritage but honour their significance to Iranian cultural history. Additionally, the martyr portrait, a class of portraiture found in both Christian and Islamic visual culture, has historically amplified the religious and political sacrifices of male life for God and country – realms in which courage is often gendered in favour of those who hold power. Sokhanvari mobilises the genre’s commemorative qualities in order to pay homage to the lives and losses of these women artists and to stitch them into the spiritual fabric of their nation’s history.

Akin to a constellation of stars hanging together discretely in space, Sokhanvari’s portraits allude to the passage of time, reflecting the differing circumstances and experiences of each woman. The changes in dress and hairstyle across each portrait point to the tastes and fashions unfolding in Pahlavi-era Iran, and the differing paths of the women wearing them. Just as cinema makes the leap from monochrome to colour, so too do Sokhanvari’s portraits, which increase in their variety of colour and pattern as the series continues. Reiterations of colour appear like a repeating chord in a musical stanza; tones of red, black and white offer connective tissue between individual women and the community of other rebels to which they belong.

The incremental additions of colour and visual complexity across the series are not neutral gestures but point to the tensions boiling in the margins of Iranian women’s lives during the pre-revolutionary period. As in the portraits of singers Ramesh (1946–2020) and Soosan (1943–2004) and actor Katayoun (b.1939), the artist captures her figures – still painted in shades of black and white – within a tangled web of thick geometric patterns in saturated tones. A dialogue ensues between the subject and her surroundings, alerting the viewer to the disconnect between these women’s lives and the duelling modalities of progress and tradition that structured Pahlavi-era Iran. Sokhanvari deploys the history of geometric patterns found in Islamic art alongside the campy, stylised aesthetics adopted in Iranian popular culture of the 1960s and 1970s, acknowledging a truly psychedelic social reality. These patterns seem to pin the women in place, reflecting the ways in which women were indeed ‘caught’ within a web of conflicting social practices; this was a web that reproduced oppressive gender roles and derailed pathways to activism and emancipation for Iranian women, many of whom were eager to fulfil the liberatory potential of the state’s progressive social mandates. Glamorous on its surface but disorienting in reality, Iran in the 1960s and 1970s affirmed Western styles but refused full equity for women in the political and cultural spheres. In a society unable to negotiate the clashes between clerics and culture-makers, women’s freedom to create and express was rendered precarious.

Sokhanvari’s portrait of Forough Farrokhzad (1934–1967) stands as a powerful example of the consequences of these social conflicts. Representing the poet as a glamorous beatnik in a black turtleneck and tousled bouffant, Sokhanvari retains the shades of black and white from the original photograph (with just a dash of lipstick for contrast) in order to memorialise all the great women lost to historical neglect. Like Saminejad, Farrokhzad’s smouldering dark eyes (a trait she shares with the black cat she cradles in her lap) provide a visual clue to her tragic story. Known for her iconoclastic poems expressing the sexual longings of women and the costs of pursuing libidinous freedom in a world organised around male desire, Farrokhzad’s publication of her work under her own name turned her into a social pariah, leading to the loss of parental rights to her son. Her early death at the age of 32 and the subsequent ban of her poems in Iran until 1989 frayed her legacy in her home country even as she ascended in international literary circles – a common fate for Iranian women artists who received recognition too late. Sokhanvari paints in egg tempera on vellum, a material made from calf hide, which carries an allusion to their role in sacrificial ceremonies. This choice of medium extends the theme of martyrdom and the violence inherent in the punishment of the young; these portraits are a call to remember those sacrificed on the altar of patriarchy.

Ever sensitive to the traumatic contexts of these women’s legacies and, in some cases, their ongoing struggles to survive, Sokhanvari engaged in extensive archival research in the preparation of these portraits, plunging into scattered repositories of Iranian popular culture and ephemera to construct fuller narratives for these women whose reputations were harmed by a biased and misogynistic media regime. Fragments of biographical details were matched to photographs and film clips now scattered across digital platforms and libraries around the world. In a few instances, quests evolved into direct contact and subsequent interviews with some of the women who are still alive, such as the former prima ballerina of the Iranian National Ballet, Haydeh Changizian (b.1945), who until recently was living in Los Angeles – a reminder of the wide reach of Iran’s diaspora and the losses and interruptions that migration across oceans and borders brings.

Rooted in research, Sokhanvari’s work emphasises the active nature of knowledge-making – a fact animated by the artist’s decision to begin her installation with a mirrored monolith and end it with a shimmering mirrored star. Just as Stanley Kubrick’s black monolith in his 1969 epic 2001: A Space Odyssey stood as an icon for human advancement, Sokhanvari likewise employs the monolith as a vow of continued learning. Covered with an ornamental explosion of stars, Sokhanvari’s monument demands a physical engagement with the viewer, whose body is incorporated and refracted by its glittering surfaces. A nod to the use of mirrored mosaic in Iranian religious architecture and the flickering conditions of the cinematic, the totem’s reflective surfaces are an invitation to contemplate these women, their stories and the consequences of their lives. Unlike Kubrick’s opaque monument, Sokhanvari’s sculpture incorporates its surroundings into itself and activates all who walk around it, leaving nothing and no one untouched. In this way, the monolith is a reminder of the active, communal nature of all feminist projects. To assemble a new history in which women are not only included, but are granted the legacies they deserve, we need remembrance, reflection and a commitment to the work of learning – within and without the gallery walls.

Sokhanvari’s emphasis on rebellion is affirmed in the title of the installation, Rebel Rebel, a nod to David Bowie’s iconic anthem to outsiders of all kinds and the undulating defiance inscribed within each portrait, each story. Although honouring these women individually, Sokhanvari makes a case that by bringing them into communion with one another, something rebellious – revolutionary, even – is rendered visible. In the West, rebelliousness is often defined in relation to the avant-garde, in which traditional boundaries of aesthetics, genres and tastes are transgressed and new space for liberatory art-making and expression is opened up. Sokhanvari’s tribute to this coterie of women reminds us of the inequities at work in mythologies of this kind, and, conversely, of the possibilities inherent in intersectional thinking – considering gender, race, class, geography, sexual preference and privileges of all kinds – to interrupt assumptions about universal freedom and reveal complexities embedded in pre-revolutionary gender politics in Iran.

Iranian women’s path towards increased social participation is neither even nor linear. It’s clear that for these women producing culture – their survival within a patriarchal society that disdained their choices – offered up new identities of rebellion, ones in which resistance to the social order was not always grand in scale or cataclysmic in consequence, but found in the sum total of many small moments of risk and refusal. In a gesture resonant with Brutalism’s mantra of ‘form follows function’, Sokhanvari has transformed a segment of the Barbican’s curving architecture into a sanctuary suitable for these revolutionary heroines. Like the soft arc of the gallery that obscures what is immediately ahead, for these women the path to creativity and expression was not smooth, nor immediately visible. Professional achievements were often accompanied by the loss of economic opportunities, excommunication from their families and communities, gendered harassment, exile and an abundance of heartbreak. To define these women as ‘rebels’, as Sokhanvari does, is to acknowledge their bravery and the ways in which they embody a form of feminist resistance led by women caught within a matrix of struggle and opportunity: a position alarmingly familiar to us today, as, like Golnar, women still need to shout their own names in defiance.

Soheila Sokhanvari: A Constellation of Stars

5 Jan 2023

Dr. Jordan Amirkhani is an art historian, curator, art critic, and educator; and was recently appointed Curator at Rivers Institute for Contemporary Art & Thought in New Orleans, Louisiana. Here she explores the life, work and influences of artist Soheila Sokhanvari.