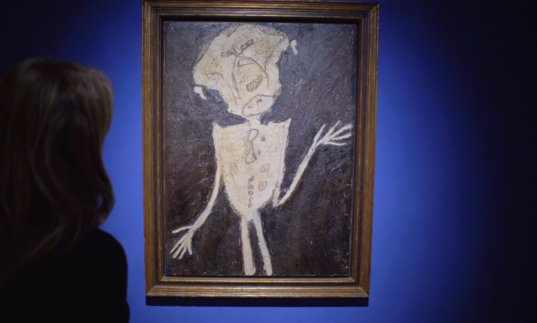

For me, art is a way of discovering and expressing myself. But Submit to Love Studios can take its members further, if they want to, through the process of exhibiting and selling their work. The purpose is partly to raise money for the studio and the artists themselves, but much more than just this, it enables members to start engaging with the sometimes challenging issue of interacting with the wider art world. Recognising your work has a commercial value, seeing it sell and hanging in a gallery can give you an intense thrill; indicating that somehow, despite all the bad things that have happened to you, your art, and therefore yourself are a valued part of wider society.

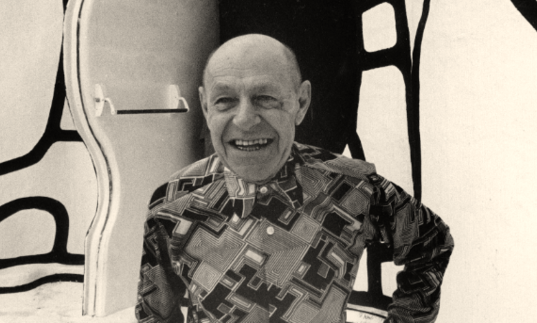

For Dubuffet in the 1940s, the art establishment was full of what he saw as stifling conventions and rules. He broke these by making his own art from unusual raw materials such as dirt and chicken poo. He used his art, and the art brut he collected, as a battering-ram to demolish high art culture, and replace it with this raw, uncooked version. He saw himself as co-ordinating a kind of art-punk revolution – doing for the visual arts what, years later, Malcolm McClaren did for music. And Dubuffet’s revolution was a very successful one. Seventy-five years later graffiti art by Jean-Michel Basquiat, Keith Haring, and Banksy are all part of the art establishment, Tracy Emin’s unmade bed and Chris Ofili’s picture made from elephant dung were sold for seven figure sums, tattoo art is everywhere (even at Wimbledon), and Dubuffet has a painting in Tate Modern, hanging near a Picasso.

In other ways though, he was less successful and even mistaken. We now see clearly that as well as high culture, there is also popular, street, advertising, and graffiti cultures, and everyone is to some extent influenced by the wider cultural world around them. For example, Phil is an artist from Submit to Love Studios. He makes collages that remind me a little of some of the works of Andy Warhol. Phil claims to not have seen his art, but he, like all of us, whether we are aware of it or not, has been drip-fed by a popular advertising culture that is greatly influenced by the art of Warhol. Phil’s art then is unconsciously influenced by a form of culture: not high culture, but street culture. Later even Dubuffet acknowledged that his quest to find in art brut, an art entirely free of culture was idealistic. For me, it is also a hopelessly romantic illusion.

Stephen is another Submit to Love artist who is much less aware of street and advertising culture than Phil. Stephen has never been able to talk and cannot understand most speech, but he takes great pleasure in making abstract paintings using blocks of colour. Stephen’s art seems to me similar to that by a very successful artist, Sean Scully, who has had exhibitions at the National Gallery and other famous places around the world. Scully, like Stephen, obsessively paints blocks of colour. The issue is not so much whether Scully and Stephen are both influenced by the same culture and society, because their influence on Stephen seems almost negligible. It becomes much more of a search for what they both have in common at the deep root of their creative process, humanity, and identity which causes them both to express themselves in similar ways (though if I was forced to choose between the two, I think I would choose Stephen’s art).