Alice Neel painted her way across a century of transformations, of momentous world events, and of personal rights and freedoms. Born in Pennsylvania in 1900, she started evening art classes as the First World War came to an end, and began painting seriously in the 1920s, in the years before the Great Depression. During the rise of fascism in Europe and the Second World War, Neel observed, engaged with, and painted the people around her home studio, first in New York’s Greenwich Village then in Spanish Harlem. Her glory years, and the start of hard-won recognition commenced in the 1960s, as the Civil Rights, Women’s and Gay Liberation movements gathered momentum.

So much for the history. What can we see – what can we read – of this woman from her work? In the 1930s we find an artist with a sense of social justice, sensitive to the impact of the Depression on New York’s poor. She observes exploited workers and mothers struggling to feed their children. In Uneeda Biscuit Strike (1936) she paints mounted police as they turn on workers protesting unfair labour conditions. Their families and neighbours look on. As witnesses they are apparently of no concern to the police, but Neel sees them.

We find Neel at a Spanish Party (1939) – watching but not dancing. She is positioned as an observer: in the scene, but somewhat apart. The dancing couples negotiate space left between a baby’s cot and a child sleeping on the sofa. It is not a wealthy room, but one animated by music. There’s music, too, in Puerto Rico Libre! (1936) – the title song, written on a sheet of paper lying between Neel and a young guitarist, who looks tired but intense. The music animating her paintings is not always the stuff of celebration – here it’s a political rallying cry.

Neel is interested in men, and curious about the portions of their anatomy usually concealed from the female gaze. In a 1932 drawing, Kenneth Doolittle lies beneath a crucifix, foreshortened like Mantegna’s fifteenth century painting of the dead Christ. Positioned at Doolittle’s splayed feet, Neel scrutinises his naked body. Beneath the hollow of his belly and sharply angled hips, the curve of his penis echoes the inward turn of the springs beneath the mattress. She’s not prissy, not proper, not worried about improprieties. Although this is an intimate bedroom scene, this phenomenon – a woman drawing a naked man from a position of desire – is a radical one. Her interest in the male body endures. Forty years later she paints John Perreault reclining on a white sheet. It’s a different dynamic: here Perreault’s nakedness is a gesture of openness, a declaration of his willingness to be ‘seen’ by Neel.

She has a wicked sense of humour. Just look at the wild painting of Joe Gould (1933) – hair flying out from his head in two licks, like the horns of a goat, naked but for his glasses, flanked by two headless male nudes. From the way the people in her paintings respond to her, she seems good company.

Neel and the century enter their forties with conflict blazing across the Atlantic. Rather than turning outward to world events, the paintings follow Neel’s gaze closer in – instead of street scenes, she’s painting individuals and families, looking deeper. Sickly and sinking into the bed, the figure in T. B. Harlem (1940) lolls, exhausted on their pillow and raises a hand to touch the new square of hospital gauze taped to their chest. Painting the titular Spanish Family (1943) Neel is fascinated by the baby – purplish and skinny legged in its bulky towelling nappy – which squirms in its mother’s arms, and eyes the painter warily. Neel paints this baby as an individual rather than an approximation. That’s what happens with this deep looking of Neel’s – she observes and drinks in figures that another brush might reduce to a symbolic presence (a baby, a TB patient.)

She’s good with children – holding their interest long enough to paint a picture (though a certain wobbliness of line tells us some wriggled more than others.) These children aren’t cute or prettified – she’s not pleasing a parent, she’s looking at people, and sometimes they are sad, or worried, or impatient. She paints Georgie Arce many times as he grows up. He holds a steady gaze, with a poise grown-ups would struggle to match. A 1955 painting of Arce sees him performing an idea of adult manliness for Neel, brandishing a knife, with a large medallion at his neck. The artist seems comfortably complicit in this performance. Although she didn’t like portrait commissions, here she paints Arce as he wishes to be seen.

There are few naked pregnant women in art history. Often they are mythic characters, or used to illustrative a moral point, rather than real women. The nymph Callisto is painted by Titian as her swelling belly is exposed and she is cast out by the huntress Diana and her followers. The blooming mother of Gustav Klimt’s Hope I (1903) is crowded by images of death and threat – an emblem of the ongoing cycle of life. Neel’s pregnant nudes, by contrast, are particular – some are resplendent, others anxious and uncomfortable. Lying on a patterned counterpane Pregnant Julie and Algis (1967) offers a spindly, doll-eyed young woman in the middle months of pregnancy. She is alert but relaxed, lying with one leg crooked. Algis beside her is fully dressed, right down to his black socks – (was it a struggle for Neel to persuade him to take his shoes off?). Margaret Evans Pregnant (1978) sits bolt upright on a little yellow chair, blue veins criss-crossing her breasts, her face held in an attitude of mild shock.

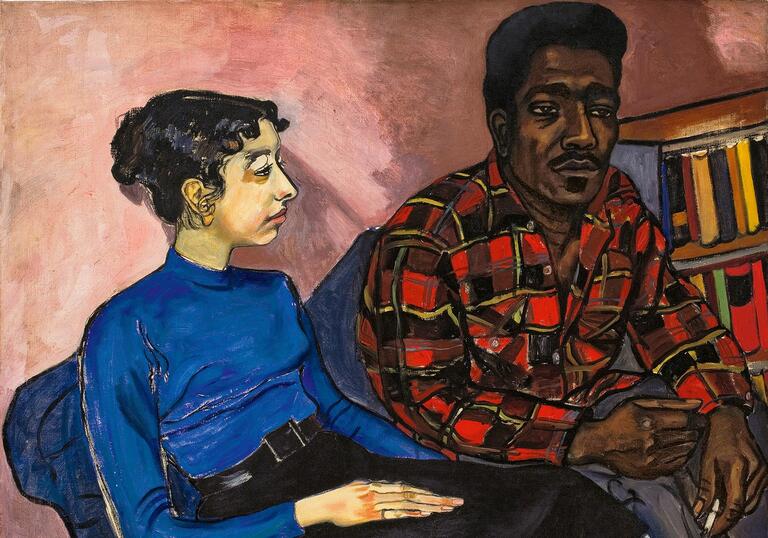

Relationships also fascinate Neel – the gaps and intersections that form between the bodies of lovers, or families, or mothers and children. In Rita and Hubert (1954) we find her looking at a young couple – intellectuals, as the shelves of books behind them seem to say. He leans forward to speak, and she watches him with a cool gaze: affectionate, interested, attentive, poised to respond with ideas in return. Their bodies are close – tightly aligned at one end of a couch, creating distance between them and Neels. Rita’s arm is lowered, and her hand tucked into the tight space between her legs and Hubert’s.

There are other lovers – they hold hands, sling arms over one another’s’ shoulders, sit huddled and intertwined. Sometimes two figures seem to occupy different paintings. One figure crowds out another. One sprawls while another sits up, alert.

Linda Nochlin and Daisy (1973) share one end of a green sofa. Like the lovers, their bodies are tightly packed together, almost knotted. The fingers of Nochlin’s right hand rest in Daisy’s lap, as she holds her daughter – whose legs dangle off the edge of sofa – gently around the middle. Neel notices the complicity between woman and girl. The exposed lengths of ankle between sock and trouser leg suggesting a shared sense of rumpled urgency. Their hands lined up, one besides the other, on the arm of the sofa. The child echoing the mother’s body language.

In Carmen and Judy (1972) Neel reimagines the Madonna and Child. This mother is no teenager. Her spindly girl baby grips at her finger and turns its cheek toward her waiting breast. Neel paints Carmen with a fleeting half smile. Over the preceding ten years, the paintings have been getting looser – she’s been leaving backgrounds empty, details of furniture sketched in with a few lines of paint, the trace of changes evident. Carmen and Judy occupy an island of colour within a white expanse of canvas.

Neel names many of the people in her paintings. Some are less remembered now, the friends, neighbours, and members of Neel’s circle – communists, writers, dramatists, thinkers. But we are familiar with the art historian and critic Linda Nochlin. We recognise Gerard Malanga (1969), a photographer and poet dressed all in black, his hair in tumbling curls, who sits for Neel with one leg slung over the arm of his chair, performing laid back sex appeal. The name Harold Cruse (c.1950) is familiar from our parents’ shelves and their dog-eared copies of his 1967 book The Crisis of the Negro Intellectual.

The way Neel translates the most familiar name – and face – feels emblematic. Neel was 70 when Andy Warhol came to sit – a tribute to her blossoming late career. (Warhol was a bellwether of fashionable concerns.) A constructed persona in a platinum blonde wig, he was, like Neel, a close observer of fellow humans and their foibles. Shirt off, he displays scars from the surgery that saved his life after he was shot. His belly is supported by a pastel-yellow corset. Warhol’s body fragments under Neel’s brush, his left knee is barely sketched in place, and a pale blue aura floats behind him, echoing the ghostly tinge of his skin. She looks at Warhol afresh, seeing the man rather than the construct. For someone so addicted to artifice, maybe it was frightening to be observed thus. He won’t hold her gaze.

Alice Neel: Hot Off the Griddle is open at the Art Gallery until 21 May 2023.

Alice Neel: An Introduction

Rita and Hubert, 1954. Oil on canvas, 86.4 × 101.6 cm. Defares Collection. © The Estate of Alice Neel. Courtesy the Estate of Alice Neel.

20 Feb 2023

Fellow humans and their foibles: writer Hettie Judah on the paintings of Alice Neel.