He begins with a Mozart fantasia in which the sense of improvisation is everywhere apparent. The key of C minor always drew from Mozart writing of heightened urgency and anguish – just think of his 24th Piano Concerto or the Piano Sonata, K457. This Fantasia (1785) begins with dramatically snaking arpeggios and disconcerting accentuation. Accents consistently dig at the music, to unsettling effect, and glimpses of major keys tend to be fleeting, at least until a central Andantino that offers respite in its major key and its calm writing. But this is banished as the music speeds up, leading back to the opening idea; the Fantasia ends as violently as it began, in an unequivocal C minor.

Ravel’s Miroirs demands a different kind of virtuosity. Written in 1905, each of its five evocatively titled pieces is a pianistic tone-poem. ‘Noctuelles’ (Night moths) is ravishingly evoked via ever-changing time-signatures and striking ornamentation. The simple title of ‘Oiseaux tristes’ (Sorrowful birds) gives little idea of the daring imagination at play, with its contrast between the heavy textures of the sombre forest and the shrill bird-calls. The mood of introversion is dispelled by ‘Une barque sur l’océan’ (A boat on the ocean), which exults in a glittering post-Lisztian virtuosity. However, its challenges, both musical and technical, are less punishing than those of the next number. The untranslatable ‘Alborada del gracioso’ (Ravel offered the approximate ‘Morning song of the clown’) is, as any pianist will tell you, a pig of a piece to bring off, not least its manic strumming effects as keyboard emulates guitar. Miroirs ends with ‘La vallée des cloches’ (The valley of the bells), in which Ravel builds arching sonorities from the tiniest of building blocks, the harmonies striking in their audacity.

The headiness of Ravel’s sound-world continues in the Scriabin. His Fifth Sonata was written just two years after Miroirs and it’s just as ground-breaking. Through his series of 10 piano sonatas Scriabin forged a path that became increasingly revelatory. The Fifth is the first in a single movement, though within that there are heady changes of mood – by turns sensual, violent, vigorous, playful and demonic. It’s also ferociously difficult – the legendary Soviet pianist Sviatoslav Richter regarded it as the hardest piece in the entire repertoire. There’s a violent urgency to it, which perhaps reflects the speed at which it was written, in mere days in late 1907. Stylistically the sonata owes a debt to Scriabin’s recently completed orchestral Poem of Ecstasy magically translating its heady atmosphere to the keyboard.

Scriabin always claimed that he was influenced by no-one. This wasn’t strictly true – who can really compose in a vacuum? – and his early music has a notable debt to Chopin, who is celebrated in the remainder of the recital. Chopin’s pupil Wilhelm von Lenz was lucky enough to hear the composer play the A flat Waltz, Op 42, and described the result as being like ‘a garland of flowers winding amidst the dancing couples’. Set in motion by a trill, you can visualise those couples embarking on some very fancy footwork (even though Chopin renders it undanceable by pitting a duple melody against the triple-time accompaniment), and the rustle of organza as the waltz speeds up in its closing moments.

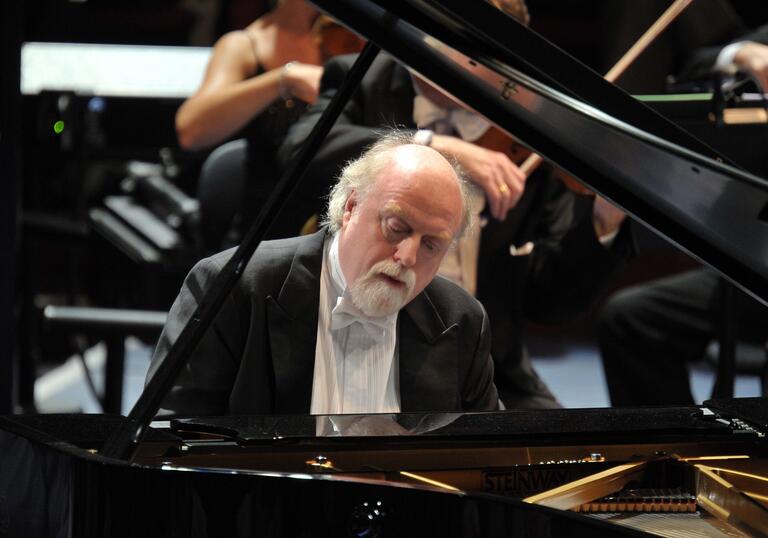

Chopin’s C minor Prelude, Op 28 No 20 proved irresistible to our two final virtuoso pianists. Both Rachmaninov, whose 150th birthday we’re celebrating this year, and Busoni found inspiration in its strong-jawed chordal sequence and its dramatic dynamic curves, starting loudly and closing at a whisper. Busoni’s work dates back to 1884, when he was just 18, but he revised it twice, and it’s the most streamlined final version that Peter Donohoe plays this evening. Modest it may be in duration but in terms of ambition this peerless composer-pianist packs a real punch. Chopin’s theme is prefaced by an introduction that is immediately recognisable as the work of Busoni, and though the theme itself is relatively straight, the first variation already shows the harmonies characteristic of the Italian master. As the work progresses through its nine variations, we are drawn more and more into Busoni’s world, though within the final scherzo section there’s a ‘Homage to Chopin’, in the form of a graceful, if short-lived waltz.

Rachmaninov’s Chopin Variations (1902–3) was his first major solo work, but how confidently he deals with both genre and scale. Again, the theme is close to the original prelude, but what’s striking is how quickly and subtly this iconic chordal theme becomes ‘Rachmaninovised’ through the ensuing 22 variations. Structurally, he creates a kind of four-movement structure (first movement, Vars 1–10; slow movement, Vars 11–18; scherzo, Vars 19 and 20; and finale, Vars 21 and 22). And though on paper it looks as if the movements are getting shorter and shorter, in fact this isn’t the case. The variations tend to get progressively longer, and the extended Var 22 breaks into a joyously confident C major peroration, the final Presto bringing the work to a close with virtuoso aplomb. It’s a remarkable tribute from one master of the keyboard to another.

© Harriet Smith