Ghosts and Whispers plunges you into a spooky and unsettling world of unfinished snippets of film and music, inviting you to ponder last thoughts, unfulfilled potential and the transience of life.

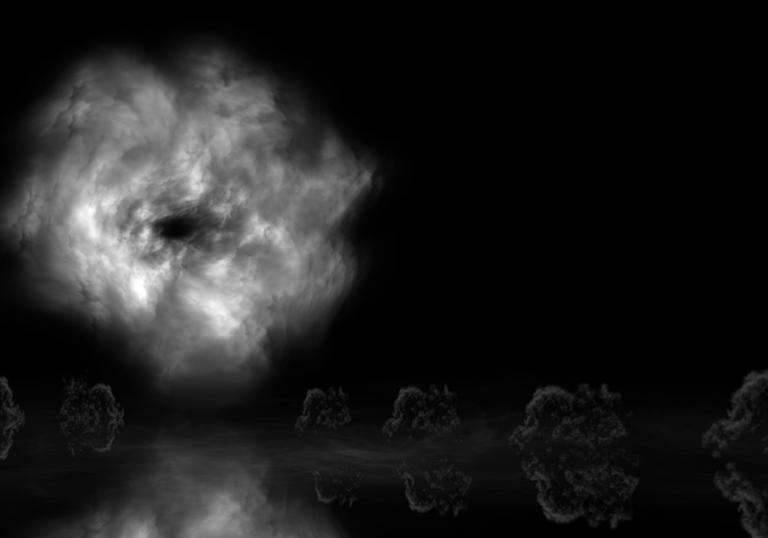

For this is no ordinary concert programme. The music selected by pianist Clare Hammond and composer John Woolrich flows between Schubert and Mozart, Wagner and Janáček, Jacquet de La Guerre and Schumann – some pieces lasting just a few moments, others several minutes, but all of them incomplete. The unsettling feeling this creates is intensified by being engulfed in darkness, and having, on the big screen in front of you, works by stop-motion masters the Quay Brothers.

‘Even though many of the pieces are buoyant or quite bright in mood, the fact that they’re fragments means there’s always this sense of potential that was never fulfilled in them,’ Hammond says.

The unfinished works are drawn from a variety of sources and interspersed with elements from Woolrich’s Pianobooks – collections of intimate, small-scale works that, despite their brevity, conjure emotional pictures in miniature.

‘Mozart was well known for keeping sketchbooks of ideas that he would return to and flesh out when a new commission came in,’ says Hammond, explaining how she and Woolrich chose the music. ‘So we’ve included some of those ideas. There are also two pieces by Janáček, such as one written on the back of his will while he was on his deathbed, addressed to his muse, called I’m Waiting For You! The other piece of his we’ve included is called Only Blind Faith, which deals with the idea that humans strive for purpose and fulfilment, love and connection. But we can only do this by maintaining a blind faith because reality can be much harsher than we can handle.’

There’s also a fragment from Stravinsky’s Symphonies of Wind Instruments, in memory of Claude Debussy, and the first, discontinued version of the opening movement of Mozart’s D major Sonata, K284.

When the Quay Brothers’ animation, with its spooky-looking mannequins and china dolls, is added into the mix, the sense of disorientation is enhanced. Their inimitable style, with its blurring of mixed live-action and stop-motion animation, drips with surrealism, the hints of dusty attic nightmares and ancient folklore underlining that sense of unease.

The identical twins explain that the music selected for this immersive experience was fundamental to their selection of film clips. ‘We have never begun a project without already having the music in advance, so in that respect, Clare provided a perfect musical scenario in which she very explicitly hinted at darkness, erasure and death in an hour-long evening of piano music which runs the gamut from the Baroque to the contemporary.

‘In truth, this was where we suddenly felt compelled to test the waters in terms of what images could find themselves complicit with. We say that only because most of these pieces of music have never previously had an image assigned to them. That was very important, as was the question of what was an acceptable image for Mozart versus what would work for Woolrich, and whether they could actually be the very same image.

‘Nevertheless, we felt compelled to experiment with what these so-called boundaries might be and to challenge their limits without any sense of impudence. The music invariably made this decision for us, but it is also an entirely subjective one.’

The filmmakers say their first impulse was to dive deep into the waters of abstract cinema, then swim to the surface for a narrative approach and create an amalgam between the two. ‘But it was Clare who established the choice and order of the music, including the deliberate interleaving of John Woolrich’s Pianobooks which were very intense insofar as they permitted us to discover images that seemed coded by a very secret narrative. We wanted all these individual fragments to elaborate themselves into one single disguise that was as concise as it was veiled between what courted narrative and then could slip into abstraction without ever once being dismissive of the music.’

The Quay Brothers, whose work is predominantly in short films, have been a mainstay of British animation for more than 40 years and their singular style has often been imitated. They found the experience of working with Hammond a ‘complete revelation’.

‘Heretofore, we had never conceived of images for a programme of solo piano, believing that the images would be revealed as far too naked. In fact, the previous two times that we have been invited to the Barbican were for films to the music of Stockhausen and Penderecki – but with Clare, the volume and size of the music has been drastically reduced, and suddenly the silences take on a majesty of their own; even in these silences another sound can be heard.’

The intensity of the spooky experience is apt as this performance falls the day before Hallowe’en. As Hammond says, the immersive feeling taps into the spirit of the true nature of the festival, before it became ultra-commercialised, with the inherent tackiness that can bring. ‘I can imagine that if you were in a culture where [ghosts] felt more real, this kind of programme would really capture something of that spirit. In some ways, it’s more authentic to the spirit of Halloween than much of what we do now.’

© James Drury