Heavy handed, we crush the moment

Curator Lotte Johnson speaks to Last Yearz Interesting Negro (Jamila Johnson-Small) about her recent commission for the Barbican, artistic collaborations and the impact of the current situation.

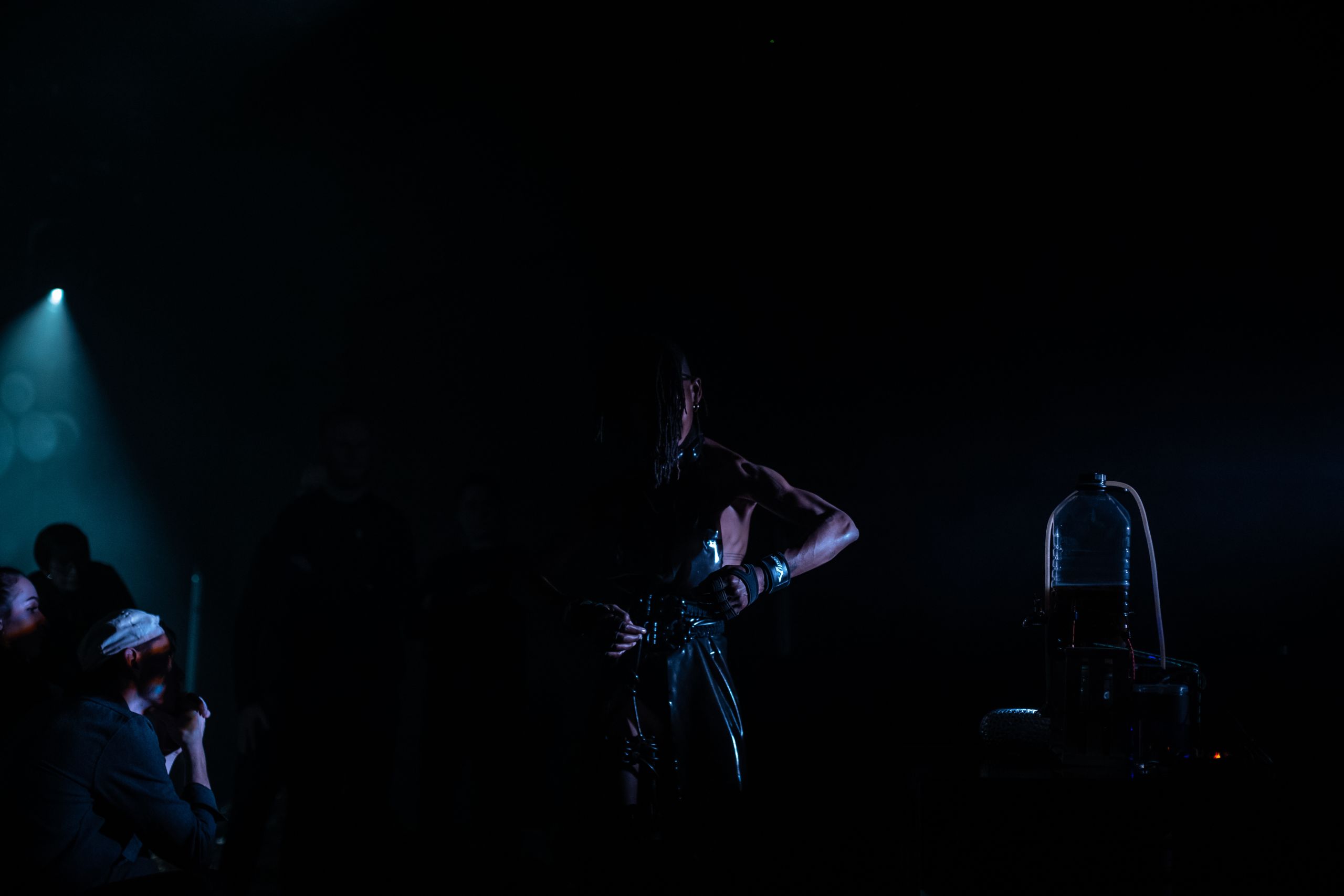

Dance, darkness and bass frequencies – Heavy handed, we crush the moment was an immersive experience, somewhere between a dreamscape, a meditation, a nightmare and a nightclub.

Over four nights last November, Last Yearz Interesting Negro presented a series of genre-blurring happenings in the Barbican’s Pit Theatre, staging a new choreographic work that featured performances by guest artists each night.

Focusing on the sensory impact of the live encounter for performers and audience alike, this work was an invitation to reflect on boundaries, intimacy, spectacle and the inevitability of movement. Last Yearz Interesting Negro and collaborators created a charged atmosphere through sound, light, set and live performance.

Working from the potential of dance as a radical social practice, this performance commission was a contemporary response to the Barbican exhibition Into the Night: Cabarets and Clubs in Modern Art.

Video content warning: strobe lights effects, partial nudity and suggestive scenes

We invited Jamila Johnson-Small to reflect on the project with the Barbican’s Associate Curator Lotte Johnson:

LJ: When you started exploring ideas for this new commission for the Barbican, we discussed your desire to create a collective space for both performers and audience members to exist within. One of many aspects that initially drew me to your work is how you are continually questioning what performance, dance and movement can mean to both performers and spectators, addressing the boundaries of spectacle and intimacy and asking how we can coexist in the same space. Can you speak about how these ideas informed Heavy handed, we crush the moment?

JJ-S: I’ve been thinking a lot about divesting spectacle off from my dancing body in performance and transferring or transmitting it to other aspects of the live situation. For example, in Heavy handed, we crush the moment, the motion of the latex costumes, their alien-skin texture and shine, their design and the cut-out exposure of our skin, took on some of the spectacle that could otherwise be directed towards our bodies/selves. As did the use of darkness and strobe lighting; the SubPacs [wearable sound technology that allowed audience members to ‘feel’ sound through physical vibrations]; and the subwoofers embedded in the rock sculptures which were seating, stage and set – giving physical stimulation to the bodies of the audience, keeping them inside their own embodied experiences and not only extending outwards to connect with ours as moving, visible performers. So the spectacle is also at play internally – not only visually – in the work, making the point that this is actually always how it is, that our imaginations and positions/postures in the world affect what we see, that our bodies are porous, and noting the intimacy and relentlessness of this.

In the studio I am working on growing awareness and attuning to what is going on inside of me (this inside also includes the outside as it moves through, settles, internalises...). This work encourages an increased sensitivity to the energies of audiences too. The weight of the eyes of others, whilst trying to access states of dancing that interest me, can be quite heavy – sometimes I experience it as almost an energetic block – because so much is going on when we look at someone. Kinaesthetic empathy is triggered, as are capacities for emotional empathy; this contact can draw me out and into an everyday kind of relation. I think of this divesting of spectacle as a strategy for these capacities for empathy to not hijack the performance (!) in order for the flow of movement to unfold. So yes, a collective space but also a space for us to each be able to be engaged with our own internal worlds – this is what I think of as coexistence.

Presenting our bodies in this ‘state of dance’, where we are attempting to ‘channel’ and allow information to flow through and out as movement, can feel very intimate, because what is being presented, necessarily, loses any sense of ‘front’. Our bodies are exposed, close, in contact. I am really interested in our layers of social performance, our coding, in how we receive others and perform ourselves daily; in shows I look for a shedding of these layers, exposure of some kind, curious as to what emerges here.

LJ: Pulsating rhythms and visceral vibrations are sensations that come to mind from experiencing the four nights of Heavy handed, we crush the moment last year. You invited several different artists to create new music, using a poem that you had shared as a starting point, and you then worked with sound designer Josh Anio Grigg to create an evolving soundscape, which changed across each evening. The resulting effect was as if there was a kind of sensory weather system changing across the course of each evening, as if a sonic organism was growing, multiplying, splitting, morphing... Can you share some insight into how these collaborations came about and why it was interesting to you for each night to be sonically different?

JJ-S: It was important for every night to be different to keep us grounded in the live, to keep us – myself and Fernanda Muñoz-Newsome [fellow performer], Josh Anio Grigg [sound designer] and Jackie Shemesh [lighting designer] – present. And to force us to work with what was coming up each evening rather than anticipating what we might think would be ‘the best’ decision for the work – we would have to let the work tell us this for itself.

One of the strategies for this was to work with a randomising algorithm. This was set to play fragments from some of the tracks each night, at varying duration and from any moment within the music, with breaks of silence – again of different lengths – between each track. The tracks would each play from a different set of speakers (arranged around the room and suspended at differing levels from the ceiling), shifting the volume and focus in the room – wanting to unsettle and crack things open a bit. It was quite a disorienting landscape to be dancing within.

I was reading an essay by Ursula Le Guin earlier and this line stood out in relation to this question: ‘The true laws – ethical and aesthetic, as surely as scientific – are not imposed from above by any authority, but exist in things and are to be found – discovered’.

I asked seven different artists to contribute to the sound and it was a beautiful process in many ways – sending my words out and then having them come back morphed into gifts of new meaning, offering new insight. I really wanted the sound to be a world of its own, but didn’t want this world to belong to any one person or any one aesthetic. I invited artists, some of whom I had worked with before, and others with whom I was in some kind of conversation, to continue our dialogue through this exchange.

LJ: At one point early on in your performance, you and Fernanda were cocooned in a latex womb suspended from the ceiling by black chains, a sculptural element of the set designed by AGF Hydra (who also designed your latex outfits). As flickering lights illuminated your forms navigating this embryonic shape, you gradually emerged out of the womb onto the floor as if into a post-apocalyptic landscape. Can you talk about your interest in states of decomposition?

JJ-S: I think of decomposition in relation to this desire to stay ‘live’. Things that are alive go through processes of decomposing that aren’t subject to human control or direction. The way that I work as a choreographer, is to try to create conditions for things to live together in a space, and for a period of time. I see that living as an unfolding or unravelling of the scenario – a mixture of clashes, confusions, attractions, encounters… a surfacing (as in, coming to the surface) between somatic presence and the elements within the environment. Things might arrive unintelligible, as a flood or dribble of language, as a strange feeling, an awkward gesture, a collection of seemingly disparate or disconnected things. An engagement of practices of imagination and association comes to give voice to unreachable or buried (yet present, affecting, driving) things.

LJ: Each evening featured interventions by a guest artist (keyon gaskin or Antonija Livingstone & Mich Cota) and a guest DJ (Planningtorock or Elijah*), in some ways harking to the line-up of a club night or gig. Can you tell us about your interest in inviting additional voices, bodies and sounds into the space and your work acting as a sort of vessel for others?

JJ-S: When offered resources and access I think it’s important to extend and expand the offer to others; I am not interested in being alone. A big part of the reason that I make work is to be in conversation, to contribute to ongoing dialogue (about the wildness of being alive, how we manage it and how context manages us…). And when the work is presented – especially in larger established institutions or festivals – the conversations I want to be having with, through and after the presentation of a work, can feel blocked by the dominant codes and language of the context.

It was working with Mira Kautto, as immigrants and animals in 2013, that we realised that to allow someone else’s programming to frame our work might stifle, suppress or erase things that were urgent for us, and we started to present our work alongside work from artists who shared our concerns, approaches, questions and/or aesthetics…

So it’s sort of an attempt to have some control of the narrative. Not because I am a megalomaniac but because the distortions offered by the dominant system aren’t helpful to the conversations I want to have, nor to the things I want to contribute to those conversations. Basic things like; I do not want to be the only performing black body in an event, I don’t want the focus to be on me as though from my body all answers can be delivered. And somewhere in there, I am also quite shy.

We (artists) are asked/invited to write, often, to contribute with words to discourse. Sometimes what comes out sounds like overblown performative politics, an over-promising that crushes the art beneath the weight of expectations that it will be able to change everything/anything. Sometimes because it is (performative politics, jargon and buzzwords dropped like names, so someone can check a box somewhere and say that they did their ‘diversity’ job, artists being pushed to bring the social change that only a restructuring of society and redistribution of resources could instigate). And sometimes because the reality is that no one can act alone to make change and there are always many behind/surrounding/accompanying/before/ahead. It feels important to make some of this interconnectedness, collaboration and influence visible through inviting many others into the fabric of a work.

keyon and Antonija were both artists I had met over the last years, whose work offers provocations and openings to consider what being an audience is. To me their work scratches holes in certain expectations or conventions of watching, and as a (mis-named) spectator I fall down those holes and land in a place where I discover new thoughts, notice different things. I tend to find work that doesn’t brand itself through a stating of its politics, but instead harnesses the mechanics – and myriad questions – of performance to embody political-social agendas, particularly appealing.

LJ: One final thought. I’m finding it hard to think about art at the moment without framing it in the context of the current situation that the world is facing. At a time when many bodies are forced to be static at home, while many bodies on the front line are forced to continually be active and therefore vulnerable, I wondered if you could share any thoughts [could be your own or others’] on the conditions of embodiment and survival in the present moment?

JJ-S: I find myself resisting, thinking or formulating any coherent thoughts around this. I feel a spooky and uncomfortable privilege right now that certain levels of precarity and instability are standard for me.

There is a rhetoric around a global solidarity through staying at home that seems to seek to unify and even out what remain unequal and unjust circumstances. What is home? What is force? Whose survival? How static is static? How many ‘front’ lines are there really?

This moment amplifies and intensifies the disregard of this system for the lives of those it dehumanises – people who are incarcerated, people who are poor, people who are disabled, people who were already sick – and a large number of these people are black and people of colour (and we know that this isn’t a random coincidence).

The ‘professional’ art worlds often erase material and experiential differences between people within the cultural sector, as we go to the same private views, and sit at the same tables drinking the same wine, and maybe this could be a time to reflect on these things. To think about and look at the ways our lives are structured by an aggressive white supremacist capitalism that continues to fail so many… to note the sneaky moves that governments are trying to pull, like the anti-abortion laws in Poland, to note the fact that prisoners due to be released to prevent overcrowding in UK prisons weeks ago still remain inside… I don’t know, I have no answers and jumbled thoughts, not all of which I am ready to look at. My friend Charlotte wears a t-shirt that reads 'No justice, no peace', I am thinking about this right now.

Image credits

Studio images: Last Yearz Interesting Negro (Jamila Johnson-Small). Heavy handed, we crush the moment, 2019. Commissioned by Barbican, London. Image: Katarzyna Perlak © Jamila Johnson-Small

Performance images: Last Yearz Interesting Negro (Jamila Johnson-Small). Heavy handed, we crush the moment, 2019. Commissioned by Barbican, London. Pictured performers: Last Yearz Interesting Negro and Fernanda Muñoz-Newsome. Image: Maurizio Martorana © Jamila Johnson-Small