Exhibition Guide:

Postwar Modern

New Art in Britain 1945-1965

Introduction

The Second World War caused suffering and loss of life on an unimaginable scale, and dislocation, conflict and upheaval continued in the twenty years that followed. This was a period marked by a nuclear dawn, the Cold War, the waning of the British Empire and the multiple convulsions that resulted from it. In Britain, there was relief at having endured and been victorious, but there was also exhaustion and the complex challenges of healing and reconciliation. Out of the fear and uncertainty came a desire to forge a better future, while the demands for equality, liberation and human rights would continue to be fought over. Artists had to make sense of an entirely altered world in which ideologies of every persuasion had been called into question, even the belief in humanity itself.

Focusing on 48 artists who experienced the war and its global aftershocks at a formative stage in their development, Postwar Modern: New Art in Britain 1945–1965 demonstrates that it was these very conditions that gave rise to extraordinary and deeply moving art in these years – an art more vital and distinctive than has tended to be recognised. The exhibition moves beyond familiar groupings of artists by ‘school’, medium or geographic origin, instead paying close attention to shared experiences and preoccupations. In a period in which Britain was redefined by migration, ‘the new’ in art-making was profoundly enriched by refugees from Nazism as well as those arriving from a crumbling empire. At the same time, Postwar Modern celebrates the work of women artists whose practices were frequently marginalised then and since.

A kind of ‘rough poetry’ underpins much of the revelatory art on display. The phrase is borrowed from the architects Alison and Peter Smithson, who used it as a way of describing the ethos of Brutalism they and others developed. Here, it resonates more broadly, capturing something of the unique sensibility of both abstract and figurative art made in Britain during these postwar years.

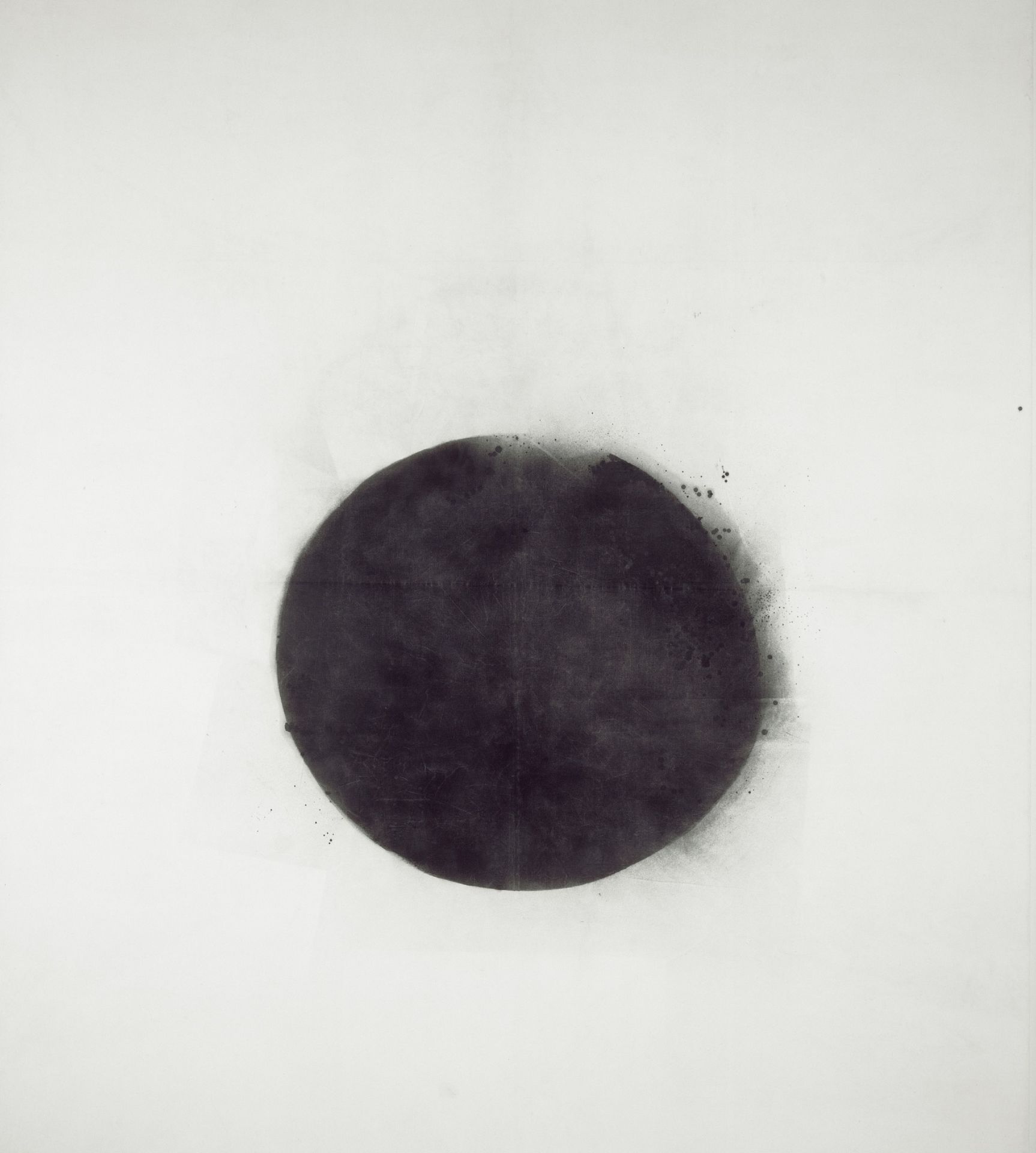

John Latham, Full Stop, 1961, Tate, © The Estate of John Latham, photograph © Tate

John Latham, Full Stop, 1961, Tate, © The Estate of John Latham, photograph © Tate

Francis Newton Souza, Mr Sebastian, 1955, Collection Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, New Delhi, © Estate of F N Souza. All rights reserved, DACS 2022, photograph by Justin Piperger, courtesy Grosvenor Gallery

Francis Newton Souza, Mr Sebastian, 1955, Collection Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, New Delhi, © Estate of F N Souza. All rights reserved, DACS 2022, photograph by Justin Piperger, courtesy Grosvenor Gallery

Body and Cosmos

Though each highly personal and distinctive, works made by John Latham, Eduardo Paolozzi and Francis Newton Souza between 1945 and 1965 share a sensibility that can be thought of as ‘postwar’. They exemplify a generational search among artists for meaning and individual agency in a fractured and unstable world, as well as a collapsing of personal and more universal trauma, that is found across Postwar Modern.

All three artists had been profoundly impacted by either the war or its global aftershocks. Paolozzi was born in Edinburgh, the son of Italian migrants; his family were Fascist sympathisers, and his father, uncle and grandfather were drowned while being deported to Canada. Latham was born in Northern Rhodesia – then, part of the British Empire, now Zambia – and came to Britain as a child. In the navy in 1941, he witnessed the shelling of a British battleship resulting in horrendous loss of life. Souza had grown up in Portuguese-administered Goa and British colonial India, where he experienced the horrors of the partition of India.

Despite their differing perspectives, Latham, Paolozzi and Souza shared a commitment to forging a uniquely modern art in the aftermath of conflict. In these artworks, the near elimination of colour invites the viewer to consider what is seen and not seen and to engage with questions of life and death, beginning and ending, creation and destruction. At the same time, there is a focus on the isolated human being as both victim and survivor, a subject that haunted the postwar imagination. Latham’s poetic and monumental Full Stop (1961) is especially emblematic of the period. Partially disintegrating, the central form evokes a solar eclipse, or perhaps a black hole. Its resounding title suggests an ending, which Latham viewed as necessary for new creativity to emerge. For him, it was only through searching beyond established systems of belief and thinking that humanity could uncover new possibilities.

Post-Atomic Garden

The bombsite was an ever-present reminder of suffering and loss in the postwar era, but it also embodied the hopes of a society desperate for renewal. This landscape of dereliction was captured in the evocative black-and-white images created by the social documentary photographer Bert Hardy. The pits and craters he depicted not only served as playgrounds for children but were inspirational for an emergent generation of artists. The extraordinary relief sculptures of William Turnbull seem to mirror this shell-shocked terrain.

Romantic notions of pastoral beauty were replaced with urban wastelands that suggested life after a nuclear attack. This post-atomic garden is haunted by richly imagined mutant beasts and plants, often fashioned from found and industrial materials. Lynn Chadwick’s airborne iron predator, The Fisheater (1951), sets the tone: it is vulnerable yet threatening, monumental and delicate at the same time. Similarly, Elisabeth Frink’s menacing, humanoid Harbinger Birds (1961) appear as guardians of this unsettling domain. A now iconic trio of experimental installations, Growth and Form (1951), Parallel of Life and Art (1953) and Patio and Pavilion (1956), produced by artists associated with the so-called Independent Group, drew on scientific imagery and were inhabited by a hallucinogenic overload of creatural and vegetal forms. One of the group’s key figures, Nigel Henderson, had (like Turnbull) served as a fighter pilot in the war, an experience that had given him a disorienting new perspective on the world. His photographs and collages zoom in and out, leading the viewer on a helter-skelter ride. These jumps between the micro and the macro also resonate with Prunella Clough’s painted evocations of pulsating energy and cellular division.

In all these works, ambiguity abounds. Is Eduardo Paolozzi’s Contemplative Object (Sculpture and Relief) (1951) a grenade, a mutant seed or an asteroid from outer space?

Lynn Chadwick, The Fisheater, 1956. Postwar Modern: New Art in Britain 1945 - 1965 Installation view Barbican Art Gallery 3 March – 26 June 2022 © Tim Whitby / Getty Images

Lynn Chadwick, The Fisheater, 1956. Postwar Modern: New Art in Britain 1945 - 1965 Installation view Barbican Art Gallery 3 March – 26 June 2022 © Tim Whitby / Getty Images

William Turnbull, Sculpture, 1956 in Postwar Modern: New Art in Britain 1945 - 1965. Installation view Barbican Art Gallery 3 March – 26 June 2022 © Tim Whitby / Getty Images

William Turnbull, Sculpture, 1956 in Postwar Modern: New Art in Britain 1945 - 1965. Installation view Barbican Art Gallery 3 March – 26 June 2022 © Tim Whitby / Getty Images

Franciszka Themerson, Eleven Persons and One Donkey Moving Forwards, 1947, Collection of the Themerson Estate, © Themerson Estate 2021

Franciszka Themerson, Eleven Persons and One Donkey Moving Forwards, 1947, Collection of the Themerson Estate, © Themerson Estate 2021

Strange Universe

In the postwar period, many artists in Britain reimagined the human body. Given what humanity had suffered, it is unsurprising that the body – whether steadfastly alone or in dialogue with others – should have found itself centre stage. Painters and sculptors presented figures that were distorted and dismembered, subjected to all manner of injury, only to re-emerge in fantastical form. In this strange universe, a motley crew of hybrids assembles, each with its own story to tell.

Fuelled by science fiction and contemporary technological advances, the cyborg – fusing the human and the machine – invaded the 1950s artistic imagination, an object of fear but also fascination and wonder. Wit and eroticism often mingled with a darker sensibility. In these works, otherworldly beings come face to face with those that seem dug from the ground; rigidly upright figures contrast with unruly painted surfaces littered with organs and orifices.

Scavenged materials, whether from wreckage yards or popular magazines, were fashioned into futuristic bodies. Wounded, collapsed and shattered forms were countered with primeval goddess imagery that celebrated fertility and rebirth; while ambiguously gendered bodies throb with mutant energy. Vulnerable but intensely present, these figures are survivors, their imperfection their strength. This proliferation of fragile beings, such as the pale marshmallow-like lovers in Franciszca Themerson’s tellingly titled Comme la vie est lente et comme l’espérance est violente (How slow life is and how violent hope, 1959), remind us of the volatility of the postwar period, when to be progressing and together was a precarious, unsteady business.

Jean and John

With the future so uncertain, the home became a symbol of stability and social reconstruction in postwar Britain. There was an emphasis, too, on the traditional family and marriage, reinforcing gender stereotypes. The paintings of Jean Cooke and John Bratby demonstrate the troubling reality that could lie behind these ideals. The two artists met and married in 1953, marking the beginning of a turbulent relationship that spanned more than twenty years.

In 1954, the year food rationing finally ended, Bratby had his first solo show in London, showing several of his ‘tabletop’ still lifes: surfaces groaning with piles of packaged food, realised in vibrant oil paint. This new brand of British realism attracted attention and was nicknamed ‘Kitchen Sink’ painting, after an essay published by art critic David Sylvester. In Bratby’s canvases, the home is depicted as a psychosexual battleground, reflecting his own attempts at domestic domination. His fame far eclipsed that of his wife, but Bratby was jealous of her talent, often destroying Cooke’s works and allowing her only three hours a day to make her art. Although she later talked openly about the violence within their relationship, their paintings also chart a close artistic dialogue, their marriage and the home their shared subject.

Through her work, and her self-portraits above all, Cooke found a means of reasserting herself; as she recalled, ‘I started painting myself the way I wanted to be seen.’ Her paintings can be uncomfortable to view, but they are revealing examples of a woman artist harnessing the power of self-expression.

Jean Cooke, Early Portrait of John Bratby, 1954, Lent by the Royal Academy of Arts, London © The Estate of Jean Cooke, photograph © Royal Academy of Arts, London; photographer: Andy Johnson

Jean Cooke, Early Portrait of John Bratby, 1954, Lent by the Royal Academy of Arts, London © The Estate of Jean Cooke, photograph © Royal Academy of Arts, London; photographer: Andy Johnson

Sylvia Sleigh, The Bride (Lawrence Alloway), 1949, Tate, photograph © Tate

Sylvia Sleigh, The Bride (Lawrence Alloway), 1949, Tate, photograph © Tate

Intimacy and Aura

The years after the war were shaped by an existential search for meaning, and many people sought to find it through intimate relationships. In the work of artists Bill Brandt, Lucian Freud and Sylvia Sleigh, interior spaces become the stage for compelling, sometimes eroticised encounters. Under their scrutiny, feminine figures convey both vulnerability and a haunting power.

Brandt had been renowned in Britain for his photo-journalism since the 1930s, but from 1945 he made a dramatic shift, beginning an intensely personal and experimental series of nude studies. Using a turn-of-the-century Kodak wide-angle camera for the first time, Brandt discovered a ‘new eye on the world’. In dimly lit Victorian rooms, time seems suspended while objects and gestures become charged with mysterious significance. Characterised by shadow, disfiguration and unsettlingly precise focus, they resonate with Lucian Freud’s early portraits of his wives Kitty Garman and Caroline Blackwood.

In a rare lecture in 1954, Freud explained his approach to painting: ‘A painter must think of everything he sees as being there entirely for his own use and pleasure.’ He added that ‘the aura given out by a person or object’ is as much a ‘part of them as their flesh’. Freud’s forensic attention to small details suggests an uneasy vigilance, revealing anxieties just below the surface. In contrast, Sleigh’s little-known portraits of her lover the art critic Lawrence Alloway offer a touching glimpse into their intimacy. Alloway appears dressed as Sleigh’s ‘bride’ in compositions that riff on Renaissance and Rococo painting. Too transgressive to exhibit until decades afterwards, these private symbols of love and commitment document the fluid gender play explored by the married artist and her younger lover.

Lush Life

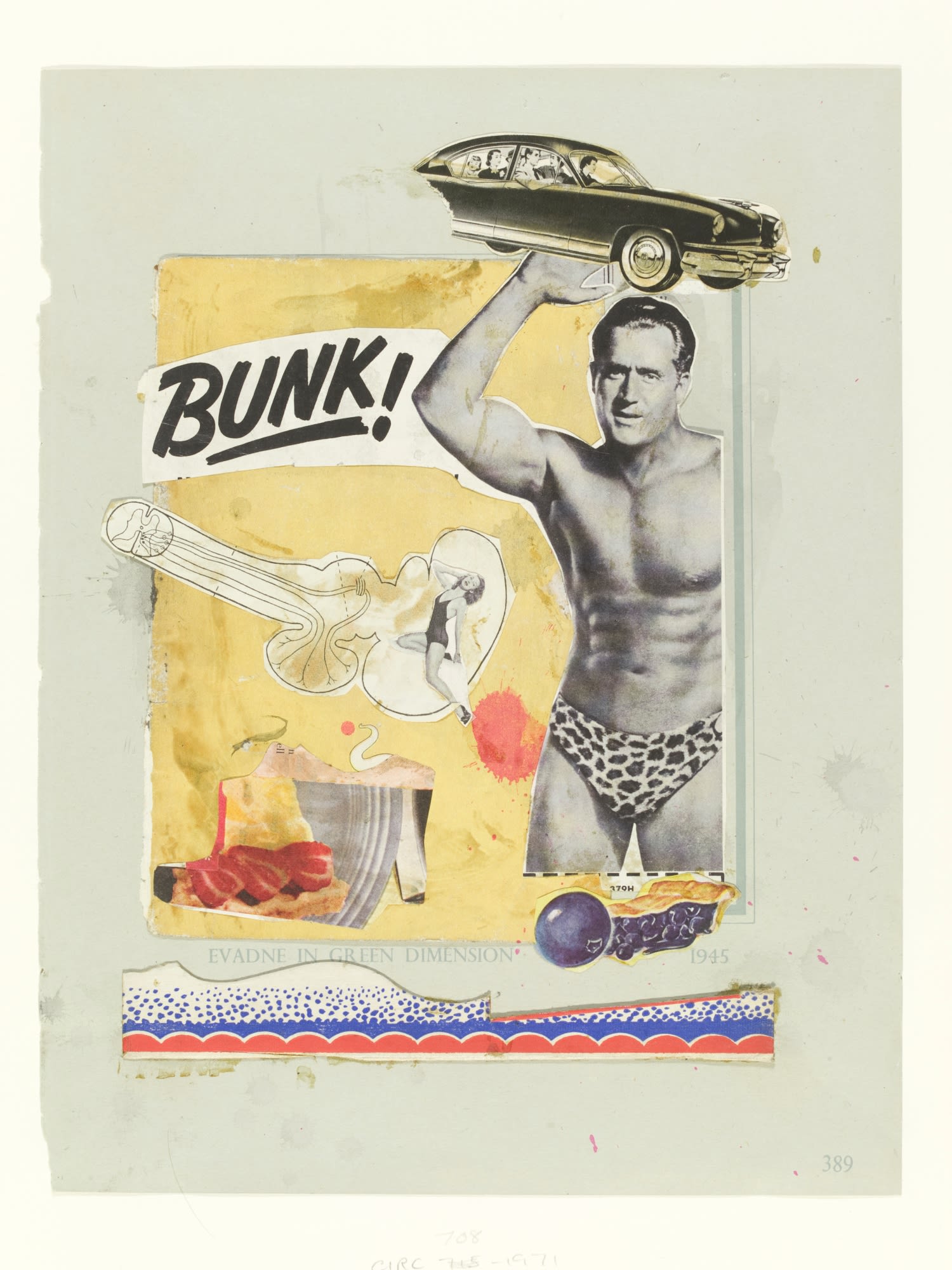

An estimated two million British homes were damaged in the Second World War, and in the austerity years that followed, household luxuries were scarce. It was not until 1954 that rationing ended in Britain, and in 1956–57 petrol restrictions had to be reimposed as a result of the Suez Crisis. The affluence seemingly enjoyed in the United States stood in alluring contrast to British life. Americans seemed to have it all: seductive cars, wall-to-wall fitted kitchens, appliances that did all the work, ice creams in different flavours, exotic breakfast cereals. All things lush and all things American – consumer objects of desire – were the focus of several artists at this time, and many explored consumerism’s relationship to femininity and domestic living. Richard Hamilton’s painting Hers is a Lush Situation (1958) is a fantasia of floating parts that scrutinises the erotic presentation of the car in marketing imagery. Eduardo Paolozzi’s ‘Bunk’ collages, which borrowed and recontextualised images from American magazines, are similarly laced with irony and humour.

In 1956, architects Alison and Peter Smithson staged a radical proposal for a new kind of living with their House of the Future, created as part of the Daily Mail Ideal Home Exhibition. Plaster, plywood and paint masqueraded as moulded plastic: undoubtedly glamourous yet decidedly strange, it was intended as a vision of the year 1981 but speaks more powerfully to its own uneasy Cold War moment. Cocooned from the outside world, the house was a space of protection, saturated with sexualised references to the female body.

Eduardo Paolozzi, Bunk! Evadne in Green Dimension, 1952, Victoria & Albert Museum, © The Paolozzi Foundation, Licensed by DACS 2021, photograph courtesy Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Eduardo Paolozzi, Bunk! Evadne in Green Dimension, 1952, Victoria & Albert Museum, © The Paolozzi Foundation, Licensed by DACS 2021, photograph courtesy Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Frank Auerbach, Head of Gerda Boehm, 1964, Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts, © The Artist. Courtesy of Marlborough Gallery, London, photograph courtesy Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts

Frank Auerbach, Head of Gerda Boehm, 1964, Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts, © The Artist. Courtesy of Marlborough Gallery, London, photograph courtesy Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts

Scars

The works of Frank Auerbach, Leon Kossoff and Gustav Metzger are among the most moving and powerful expressions of the postwar sensibility. As Jews heavily impacted by the war, they seemed each in their own way driven to make art that was potent and impassioned, seizing an agency of which they had seen others deprived.

Following the Blitz, the gaping scars in the urban landscape became sites of reconstruction on a vast scale; for the young Auerbach and Kossoff, it was an experience of the near sublime. They saw in London’s wreckage the exhilarating potential of renewal and opportunity: a wounded city on the cusp of rebirth. Close friends and collaborators in the 1950s, Auerbach and Kossoff favoured a process of lengthy observation, thickly layering earth-toned paints in an attempt to capture the flux of emotion and experience. Each devoted themselves to subjects they were deeply familiar with – and in painting them became more so. This was as true of friends, lovers and family members as it was of the urban spaces to which they compulsively returned. Kossoff’s paintings of St Paul’s Cathedral speak of the city’s endurance through wartime onslaught, while Auerbach’s building site studies emphasise the raw geometry of new structures rising out of chaos.

Leaving conventional painting behind, Gustav Metzger pioneered an art of ‘auto-destruction’ in the late 1950s: works that enacted their own disintegration, mirroring the violence he perceived in a society bent on its own destruction. A 1961 performance on London’s South Bank was captured on film. Wearing a gas mask, with St Paul’s in the background, he sprayed acid onto canvas, which shrivelled and dissolved. This was not art as object but rather art as an event, one that Metzger thought of as a rallying cry and an ‘alert’ to the dangers ever-present in society.

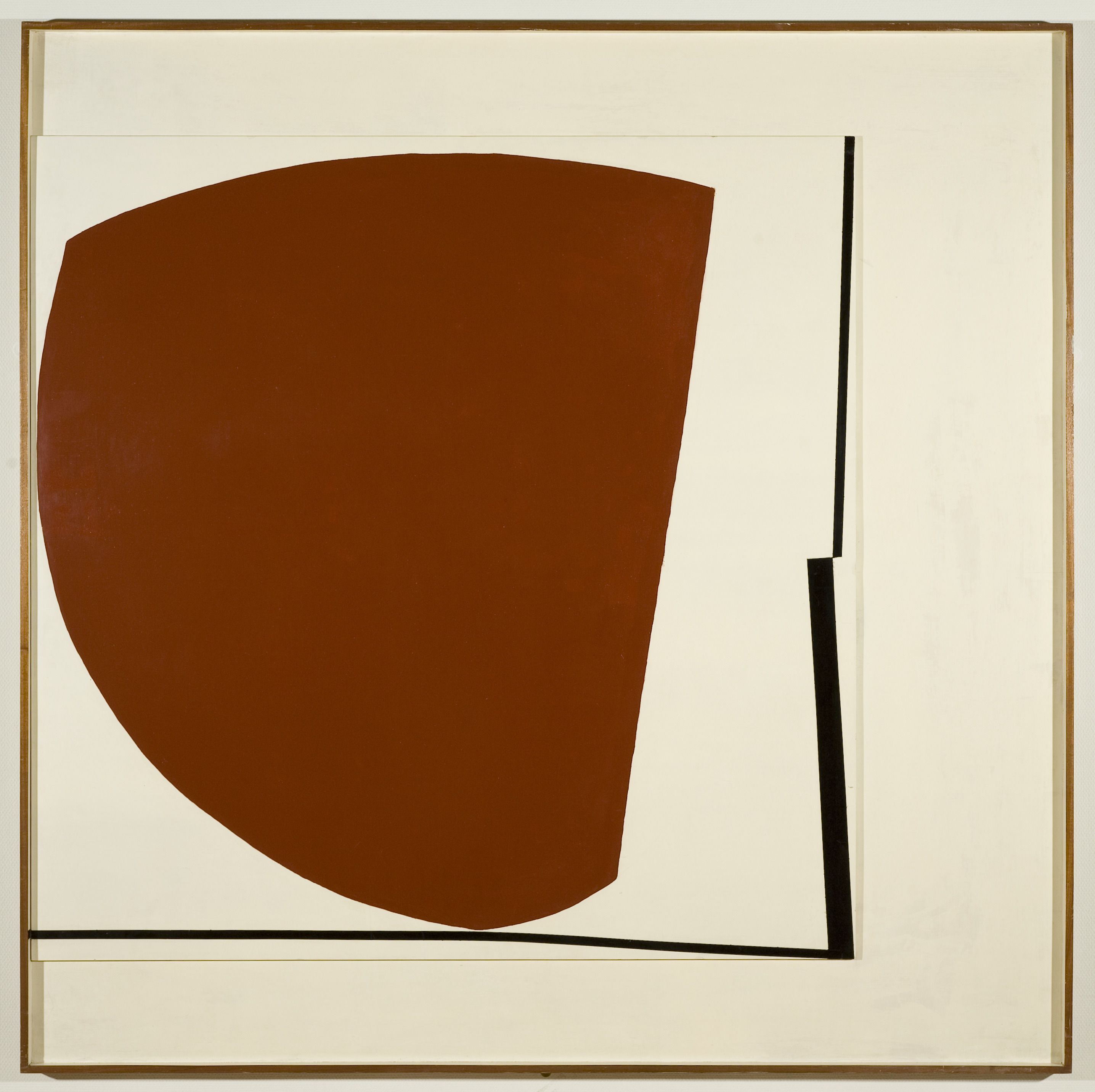

Concrete

Previously a celebrated figurative painter, Victor Pasmore underwent a radical conversion to abstract art in the late 1940s that sent ripples of controversy through the British art community. Highly charismatic, Pasmore had by 1951 established a circle of younger artists who were equally committed to the cause of geometric abstraction, which they referred to variously as ‘Concrete’, ‘Constructionist’ or ‘Constructivist’ art. These artists – Mary Martin, Adrian Heath, Anthony Hill, Robert Adams and Denis Williams, among others – became closely associated with one another for much of the 1950s, organising group exhibitions and publications.

Rather than abstracting from the visible world, they sought to ‘construct’ from first principles, understanding and replicating the essence of beauty through the study of science and mathematics. These artists pursued geometric harmonies in the search for a democratic, universal language that could transcend human differences. Critic and curator Herbert Read argued that, faced with devastation in Britain and abroad, ‘The Constructivists turned away from the ruins to create new values, to create the images of a civilisation not yet born.’

The group felt that art was for the benefit of society and that it was important to integrate it as much as possible into daily life. This desire to disrupt the exalted status of the work of art and bring it into the ‘real’ world informed the shift of Pasmore, Hill, Martin and others from painting to three-dimensional relief panels, and their choice of humble, industrial materials such as sheet metal, Perspex and household paint.

While several of the group emphasised the rationalism in their work, in reality their faithfulness to pure, ‘objective’ geometry was overstated. In fact, the poetic instinct continued to play out in works that embody the off-kilter, ever so slightly wonky sensibility found across British art of the time.

Victor Pasmore, Red Abstract No. 5, 1960 © The Estate of the Artist, courtesy of Marlborough Gallery, London, photograph courtesy Bristol Museum & Art Gallery

Victor Pasmore, Red Abstract No. 5, 1960 © The Estate of the Artist, courtesy of Marlborough Gallery, London, photograph courtesy Bristol Museum & Art Gallery

Roger Mayne, A Girl Jiving in Southam Street, London, 1957, J. Kasmin, © Roger Mayne Archive / Mary Evans Picture Library

Roger Mayne, A Girl Jiving in Southam Street, London, 1957, J. Kasmin, © Roger Mayne Archive / Mary Evans Picture Library

Choreography of the Street

The texture and colours of London’s urban architecture – its graffiti, advertising and time-worn, battered surfaces – were a source of rich artistic inspiration. The destruction and neglect suffered by inner cities resonated powerfully with the postwar mood of anxiety and loss, but could also represent a rebellious counterpoint to social conservatism.

Against this backdrop, a postwar generation was emerging and taking ownership of the streets. Nigel Henderson’s and Roger Mayne’s photographs joyously capture the higgledy-piggledy exuberance of children at play and the preening, pouting and posing of teenagers. But even as they overflow with a lively energy, these images carry a certain uneasiness, alluding to the precariousness of life amid the ruins of austerity Britain. Created between 1956 and 1961, Mayne’s most famous body of work centred on the diverse working-class community of Southam Street in North Kensington, west London. One of these photographs was used for the cover Colin MacInnes’s novel Absolute Beginners (1959), which portrayed a new confidence and attitude among Britain’s youth, but also the simmering racial tensions that erupted in the Notting Hill Riots of 1958.

The vitality of street life is mirrored in Eduardo Paolozzi’s and Robyn Denny’s collages and in the radical print designs created by Henderson and Paolozzi for their company Hammer Prints Ltd (1954–62). Fabrics and wallpapers with names such as ‘Coalface’ and ‘Sgraffito’ transformed scavenged textures of the postwar city into homewares, bristling with modernity.

Two Women

Fleeing Nazi Germany aged nine, Eva Frankfurther experienced the sense of displacement that defined the lives of so many migrants at this time, and she developed a profound compassion for those living on the social margins. Although she trained at Saint Martin’s School of Art, Frankfurther became disillusioned with the London art scene and chose to support herself as a painter by non-artistic means. She sought places that fostered a sense of community, and in 1951 began working at the Lyons Corner House in Piccadilly. Lyons was a hive of activity, employing workers from all over the world; while the work was laborious, the bustling tea shop environment provided Frankfurther with ‘boundless material in the way of human beings’.

Shirley Baker grew up in Manchester, where the urban fabric was drastically changing in the 1950s and 1960s. With the development of the welfare state came a drive to improve poor and working-class housing conditions and repair bomb damage: as a result, entire streets and neighbourhoods disappeared and families were uprooted due to slum-clearance schemes. Baker recalled, ‘nobody seemed to be interested in recording the face of the people or anything about their lives’, so she began documenting this vanishing urban landscape, always carrying a camera in her bag ‘just in case’. The summer of 1965 saw her experiment with colour photography, making a series of around 60 prints using Kodachrome 64 film. With their vibrant colour, they offer a rare view of the vitality of Hulme, Manchester during this pivotal moment.

Frankfurther and Baker shared a commitment to capturing marginalised lives with warmth and humour: their works celebrated their local communities, recording individuals who would otherwise have been lost to history. At a time when women were discouraged from becoming photographers or artists, they blazed a trail.

Eva Frankfurther, West Indian Waitresses, c.1955, Ben Uri Collection, presented by the artist’s sister, Beate Planskoy, 2015, © The Estate of Eva Frankfurther, photograph by Justin Piperger, courtesy Barbican Centre

Eva Frankfurther, West Indian Waitresses, c.1955, Ben Uri Collection, presented by the artist’s sister, Beate Planskoy, 2015, © The Estate of Eva Frankfurther, photograph by Justin Piperger, courtesy Barbican Centre

Francis Bacon, Man in Blue I, 1954, Collection Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam, © The Estate of Francis Bacon. All rights reserved. DACS 2022 © photograph Studio Tromp, courtesy Collection Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam

Francis Bacon, Man in Blue I, 1954, Collection Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam, © The Estate of Francis Bacon. All rights reserved. DACS 2022 © photograph Studio Tromp, courtesy Collection Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam

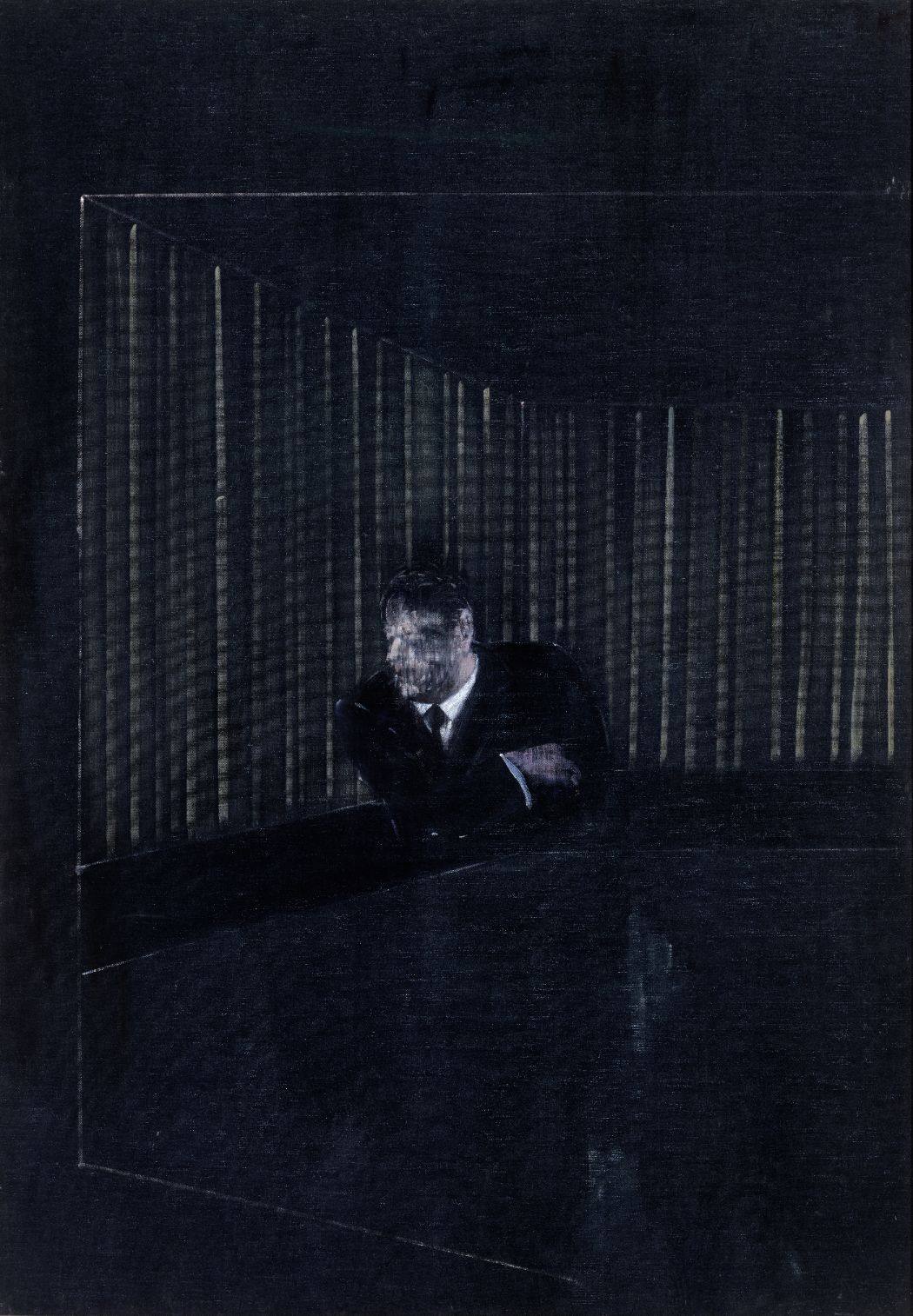

Cruise

Cruising, or looking for a casual sexual encounter in a public place, was central to the expression and exploration of male same-sex love and desire in the postwar years, as sexual acts between men remained illegal until decriminalisation in England and Wales in 1967. Francis Bacon’s Man in Blue series (1954) can be understood in the context of the moral panic around closeted homosexuality in that decade: the notion that a gay man could be hiding in plain sight. To be near his lover at the time, Bacon was living at the Imperial Hotel in Henley-on-Thames, Oxfordshire, a grand Victorian establishment with a reputation for sexual liaisons. His set of seven paintings – three of which are shown here – of an unidentified, suited man at a bar creates an unsettling atmosphere of pent-up emotion and isolation.

Urban cruising also inspired works by the younger artist David Hockney. ‘What one must remember about some of these pictures,’ Hockney commented later, ‘is that they were partly propaganda of something I felt hadn’t been propagandised … homosexuality. I felt it should be done.’ Though painted only a few years after Bacon’s series, their mood is very different: with wit and humour, they celebrate Hockney’s life as a young gay man in London and New York. In these sizzling early works, full of humour and innuendo, text plays a game of hide and seek, tongue-in-cheek phrases jostling for the viewer’s attention. The title My Brother is Only Seventeen (1962) was derived from graffiti that Hockney read on the toilet walls of Earl’s Court station, a popular cruising spot. These coded inscriptions illustrate the forced concealment of homosexuality at the time.

While shining a light on society’s prejudices and restrictions, these works also show how both artists found ways to record their experiences of intimacy and love.

Surface / Vessel

In contrast to the angst that dominated art-making in the early postwar years, works of the later 1950s and early 1960s often conveyed a dreamlike sensuality and tactility, their serenity offering refuge and comfort in a world still at sea.

In paintings by William Scott and ceramic vessels by Lucie Rie and Hans Coper, colour recedes and textured surfaces and irregular forms take centre stage. ‘I find beauty in plainness’, commented Scott in 1947, and his works – which take the domestic still life as a starting point – celebrate this enduring belief. Despite their apparent simplicity, Scott creates luminous surfaces with a profound relationship to the handmade and to natural materials.

Having trained as a potter in her native Vienna, Lucie Rie fled Austria in 1938 and settled in London, where she set up a studio in a small mews house in Bayswater. Rie expressed her sophisticated, modernist sensibility in fragile stoneware and porcelain vessels, always thrown at the wheel. Highly refined, with elongated gently asymmetrical lines, her quivering, thinly potted forms embody a rare elegance. In contrast to the delicacy of Rie’s work, Coper’s has a more emphatic sculptural presence, sometimes articulated on a monumental scale. Another refugee from Nazism, Coper joined Rie’s studio as an assistant in 1946, his artistic talents becoming quickly apparent. He worked frequently with grainy white stoneware clay, throwing pots on the wheel and often fusing them together as powerful composites. By the 1950s he had developed a mature language of boldly simplified forms with sensuously weathered, earth-toned surfaces.

Lucie Rie, Vase, 1960, Estate of the Artist, photograph courtesy Crafts Council

Lucie Rie, Vase, 1960, Estate of the Artist, photograph courtesy Crafts Council

Patrick Heron, June Horizon, 1957, Wakefield Council Permanent Art Collection (The Hepworth Wakefield), © The Estate of Patrick Heron. All rights reserved, DACS 2022, photograph courtesy The Hepworth Wakefield

Patrick Heron, June Horizon, 1957, Wakefield Council Permanent Art Collection (The Hepworth Wakefield), © The Estate of Patrick Heron. All rights reserved, DACS 2022, photograph courtesy The Hepworth Wakefield

Liberated Form and Space

In the later 1950s, the shadow cast by conflict and loss began to give way, for some, to lightness and saturated colour. A new sensibility emerged in both sculpture and painting: a freeing of form and space, defined by buoyant, sensual shapes and a heightened materiality. Universal geometries such as the circle and the square feature prominently along with abstract constructions, but now expressed with a certain warmth and irregularity so that they vibrate and hum with a sense of energy and opportunity.

Many artists at this time were inspired by American Abstract Expressionism, while others drew on non-Western and pre-modern visual sources. By the early 1960s, Gillian Ayres was combining the possibilities of liquid dribbles, splashes and stains with forms loosely sketched onto the canvas. Anwar Jalal Shemza’s lyrical paintings fused the ornate patterning found in Islamic architecture and calligraphy with the language of international modernism. Meanwhile, Kim Lim’s practice was informed by her extensive travels in East and Southeast Asia: she distilled shapes and forms that she had encountered into powerful carved sculptures that leave the process of their making exposed.

The paintings of Patrick Heron blossomed into rapturous planes of colour. In 1956, he remarked on the liberation he felt by moving into abstraction, saying, ‘I now explore with a sense of freedom quite denied me while I had to keep half an eye on a “subject”.’ By the mid-1960s, Frank Bowling’s work had also undergone transformation. Big Bird (1965) shows the artist forging an expansive visual language that was distinctly his own: large in scale, incorporating both figurative and abstract elements, and realised in brilliant colour. Beating its wings frantically against a geometric sky, the swan is both soaring upwards and tumbling to earth.

Horizon

A decade often characterised by hedonism, psychedelia and brilliant technicolour, the 1960s saw rapid social and political changes and an explosion of artistic experimentation. The work of David Medalla and Gustav Metzger developed postwar preoccupations in new directions, demonstrating the transformative vitality of the period.

In the early 1960s, Medalla and Metzger were among the co-founders of London’s Signals gallery. A groundbreaking space devoted to radical interdisciplinary practice, Signals was dedicated to ‘adventures of the modern spirit’. Disciplines ranging from politics, engineering and literature were being woven into an entirely new artistic language that resonated with the shifting social landscape and technological advances of the 1960s. The potential of moving sculpture fascinated Medalla, who created artworks using fluid, organic materials like sand, bubbles, mud and smoke. In 1963 he made his first Sand Machine sculptures: rotating structures that choreograph fragile forms in space, only to instantly unmake them. Medalla was interested in material transformation, both in a poetic and scientific sense.

A similar emphasis on raw and ephemeral materials defines Gustav Metzger’s sculpture, which had political activism at its heart. Metzger fled Nazi Germany as a child and later became deeply involved in the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament. By the early 1960s, he was moving away from what he called ‘auto-destructive art’, which held up a mirror to a violent world, towards ‘auto-creation’, in which the work of art takes on its own life. Liquid Crystal Environment (1965) was created using heat-sensitive chemicals sandwiched between rotating glass slides in a projector. A landmark work of immersive installation, its undulating chromatic patterns perhaps evoke the mushroom clouds of nuclear war but also a seductive future of limitless change and possibility.

Gustav Metzger, Liquid Crystal Environment in the Postwar Modern: New Art in Britain 1945 - 1965 Installation view Barbican Art Gallery 3 March – 26 June 2022 © Tim Whitby / Getty Images

Gustav Metzger, Liquid Crystal Environment in the Postwar Modern: New Art in Britain 1945 - 1965 Installation view Barbican Art Gallery 3 March – 26 June 2022 © Tim Whitby / Getty Images

Gillian Ayres, Break-off, 1961, Tate, © The Estate of the Artist courtesy of Marlborough Gallery, London, photograph © Tate

Gillian Ayres, Break-off, 1961, Tate, © The Estate of the Artist courtesy of Marlborough Gallery, London, photograph © Tate

Featured Artists

Adrian Heath (b. Matmyo, Burma) (1920 – 1992)

Alan Davie (b. Grangemouth, Scotland) (1920 – 2014)

Alison Smithson (b. Sheffield, England) (1928 – 1993)

Anthony Hill (b. London, England) (1930 – 2020)

Anwar Jalal Shemza (b. Shimla, India) (1928 – 1985)

Aubrey Williams (b. Georgetown, Guyana) (1926 – 1990)

Avinash Chandra (b. Shimla, India) (1931 – 1991)

Bert Hardy (b. London, England) (1913 – 1995)

Bill Brandt (b. Hamburg, Germany) (1904 – 1983)

David Hockney (b. Bradford, England) (b. 1937)

David Medalla (b. Manila, Philippines) (1942 – 2020)

Denis Williams (b. Georgetown, Guyana) (1923 – 1998)

Eduardo Paolozzi (b. Edinburgh, Scotland) (1924 – 2005)

Elisabeth Frink (b. Great Thurlow, England) (1930 – 1993)

Eva Frankfurther (b. Berlin, Germany) (1930 - 1959)

Francis Newton Souza (b. Goa, India) (1924 – 2002)

Francis Bacon (b. Dublin, Ireland) (1909 – 1992)

Franciszka Themerson (b. Warsaw, Poland) (1907 - 1988)

Frank Auerbach (b. Berlin, Germany) (b. 1931)

Frank Bowling (b. Bartica, Guyana) (b. 1934)

Gillian Ayres (b. Barnes, London) (1930 – 2018)

Gustav Metzger (b. Nuremberg, Germany) (1926 – 2017)

Hans Coper (b. Chemnitz, Germany) (1920 – 1981)

Jean Cooke (b. London, England) (1927 – 2008)

John Bratby (b. London, England) (1928 – 1992)

John Latham (b. Livingstone, Zambia) (1921 – 2006)

John McHale (b. Glasgow, Scotland) (1922 – 1978)

Kim Lim (b. Singapore) (1936 – 1997)

Lee Miller (b. New York, USA) (1907 – 1977)

Leon Kossoff (b. London, England) (1926 – 2019)

Lucian Freud (b. Berlin, Germany) (1922 – 2011)

Lucie Rie (b. Vienna, Austria) (1902 – 1995)

Lynn Chadwick (b. London, England) (1914 – 2003)

Magda Cordell (b. Hungary) (1921 – 2008)

Mary Martin (b. Folkestone, England) (1913 – 1990)

Nigel Henderson (b. London, England) (1917 – 1985)

Patrick Heron (b. Leeds, England) (1920 – 1999)

Peter King (b. London, England) (1928 - 1957)

Peter Smithson (b. Stockton-on-tees, England) ) (1923 – 2003)

Prunella Clough (b. London, England) (1919 – 1999)

Richard Hamilton (b. London, England) (1922 – 2011)

Robert Adams (b. Northampton, England) (1917 – 1984)

Robyn Denny (b. Abinger, England) (1930 – 2014)

Roger Mayne (b. Cambridge, England) (1929 – 2014)

Shirley Baker (b. Manchester, England) (1932 – 2014)

Sylvia Sleigh (b. Llandudno, Wales) (1916 – 2010)

Victor Pasmore (b. Chelsham, England) (1908 – 1998)

William Scott (b. Greenock, Scotland) (1913 - 1989)

William Turnbull (b. Dundee, Scotland) (1922 – 2012)

Postwar Modern: New Art in Britain 1945 - 1965 Installation view Barbican Art Gallery 3 March – 26 June 2022 © Tim Whitby / Getty Images

Postwar Modern: New Art in Britain 1945 - 1965 Installation view Barbican Art Gallery 3 March – 26 June 2022 © Tim Whitby / Getty Images

Associate Artitst:

Abbas Zahedi

Age of Many Posts

3 Mar – 26 Jun

Age of Many Posts is an expanded public programme curated by Associate Artist Abbas Zahedi. Commissioned to work in parallel to Postwar Modern, Zahedi will explore the resonances between our current moment and the reality faced by artists working in the twenty years following the Second World War. Encompassing an open studio, public tours, talks and events, cinema screenings, performances and a Young Barbican Weekender, Zahedi will respond directly to artists, artworks and themes presented in the exhibition.

While Postwar Modern explores art produced between 1945 and ’65, its context resonates keenly with now. As the UK emerges from more than a decade of austerity, the socio-cultural reverberations of Brexit, and ongoing struggles and upheavals in the campaign for racial and gender equality, while facing the challenges of a global pandemic and the climate emergency, we are asking similarly probing questions about what kind of society we want and need to be.

Collaborating with teams across the Barbican including Creative Learning, Cinema, Music and communities local to the Centre, Zahedi seeks to explore these contemporary similarities through ongoing conversations with multiple individuals, illuminating the exhibition, artists and artworks in new and exciting ways.

Sonic Support Group attendee, as part of Ouranophobia SW3 by Abbas Zahedi, Chelsea Sorting Office, 2020-2021. Photo courtesy of the artist.

Sonic Support Group attendee, as part of Ouranophobia SW3 by Abbas Zahedi, Chelsea Sorting Office, 2020-2021. Photo courtesy of the artist.

Shop the exhibition

The exhibition is accompanied by a fully illustrated catalogue, published by Prestel and designed by The Bon Ton. It includes new essays by Jane Alison, Hilary Floe, Ben Highmore, Hammad Nasar and Gregory Salter alongside a newly commissioned illustrated chronology documenting the period.

Prints from the exhibition are also available to purchase in the Art Gallery Shop or online.