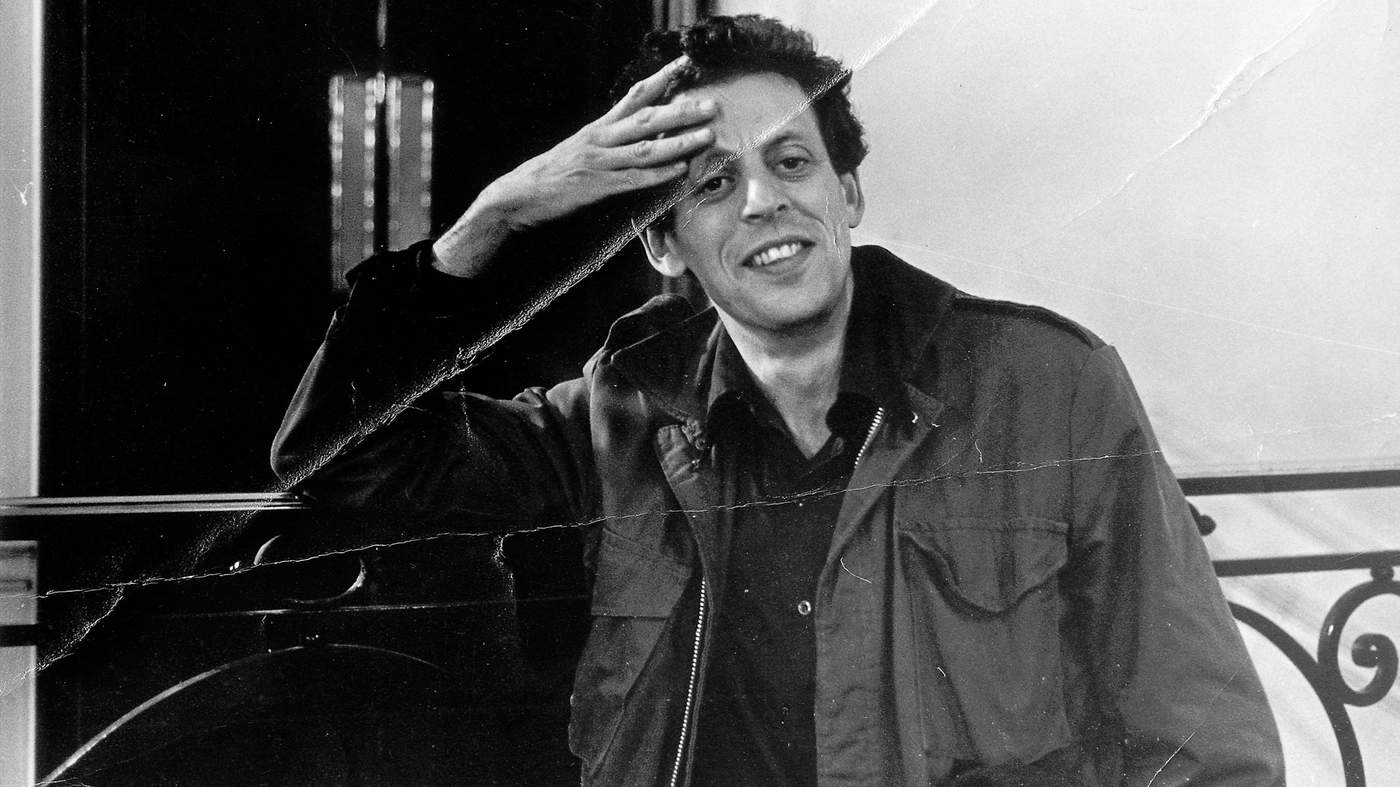

Reich once said about popular music that ‘it comes and it goes’, but he fell under its spell at an early age, as did Glass and Adams. Reich’s mother was a singer-songwriter and lyricist who wrote tunes for Broadway shows during the 1930s and 40s. Before entering Cornell University, at only sixteen, to study philosophy, Reich immersed himself in jazz, heading down to Manhattan from the leafy suburbia of Larchmont, New York, during the early 1950s to hear Miles Davis, Bud Powell and Kenny Clarke. Bebop drummer Clarke was especially influential, and for a few years Reich harboured aspirations of becoming a jazz drummer himself. The notion of a propulsive groove serving as a musical work’s rhythmic backbone has formed an integral part of Reich’s musical language ever since.

Glass entered college at an even younger age – fifteen – arriving at the University of Chicago having studied flute at the Peabody Conservatory in his hometown, Baltimore. Like Reich, he also took philosophy, alongside mathematics, but spent his evenings in the jazz clubs on fifty-fifth street, listening to Charlie Parker, John Coltrane and Thelonious Monk.

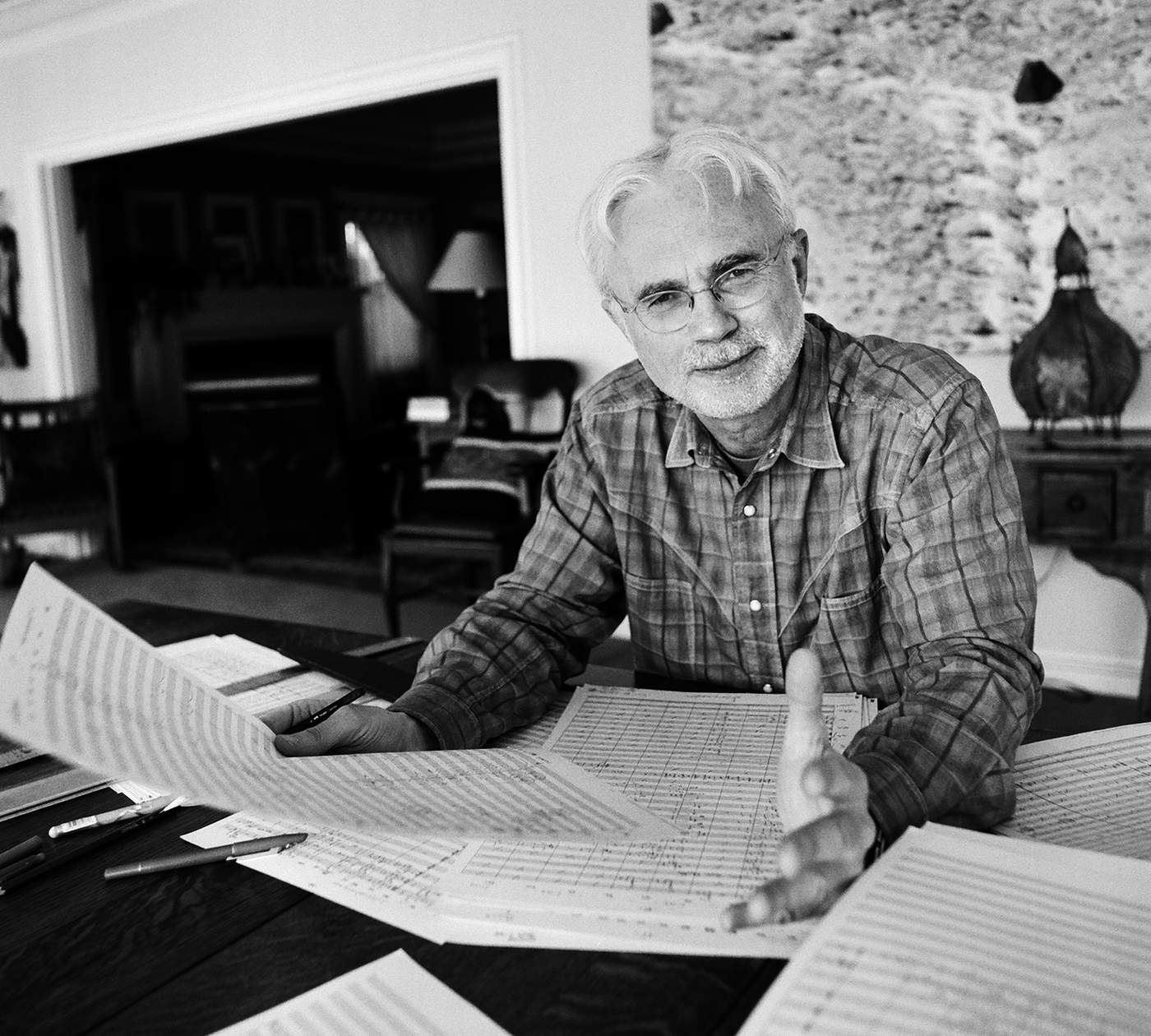

Adams’s parents were keen amateur musicians – his father played clarinet and saxophone while his mother sang – who both performed in big bands around Lake Winnipesaukee in New Hampshire. Adams’s route into music was more direct. Having gained a music scholarship to Harvard University, ostensibly to study conducting and develop his skills as a clarinettist, Adams studied twelve-note music by day while listening to jazz, rock and soul by night.

In other respects, the backgrounds of the three composers could not be further apart. Although his parents divorced when he was very young, Reich was raised in New York City in comfortable upper-middle-class surroundings (his father was an attorney). Glass came from a working class background. His father ran a radio repair shop in downtown Baltimore, which in time was turned into a record store. Thus Glass was exposed to a wide variety of music from a young age. Some of it was of a rather recherché nature, too, as Glass’s father brought home recordings of music he couldn’t sell in the store. Unlike Reich and Glass’s urban upbringings, Adams was brought up in rural East Concord, New Hampshire, with a population of just 300.

Photo: Steve Reich © SiSi Burn

If Glass’s musical ‘double life’ included working with Shankar while producing counterpoint exercises for Boulanger, during the early 1970s, Adams’s double life at Harvard involved composing twelve-note music for his composition teachers during the day while listening to Jim Morrison and The Doors or Eric Clapton’s Cream by night. In an attempt to reconcile these differences, Adams headed – as Reich had done a decade or so earlier – to San Francisco, armed with a copy of John Cage’s influential book Silence. Soon, Adams started to develop his own musical voice, initially through collage, quotation and experimentation, such as in the neo-Ivesian American Standard (1973), but also by harnessing the rhythmic energy and harmonic stasis of minimalism to his own, far more eclectic and intuitive ends.

Adams later stated that ‘minimalism is only a fraction of my musical life’, and his music’s architectonic dimensions, large-scale tonal designs, temporal sweep and vivid orchestration owes as much to Debussy and Ravel as it does to minimalism. In fact, paradoxically all three composers’ musical languages have been moulded by outside influences. It is worth noting that the sounds that now epitomise America were drawn from cultures and traditions far beyond its borders.

Just as Debussy’s music leaves an indelibly ‘French’ imprint on its audience, so does Adams’s music sound unequivocally ‘American’.

His music lives and breathes a kind of present-tense America, one which – in operas such as Nixon in China (1985–7) or the controversial The Death of Klinghoffer (1991) – possesses the same sense of immediacy and urgency one gets from a CNN news bulletin. There is of course far more to Adams’s music than recasting historical and political ‘fact’ through music. His powerful yet restrained On the Transmigration of Souls (2002) was one of the first works by a major composer to respond to ‘9/11’.

Not every work by Adams is set in contemporary America. His 2006 opera A Flowering Tree is based on an Indian folk tale, for example, but more often than not Adams’s music is shaped by America’s people, history, politics and landscape. Even the early Shaker Loops (1978) looks back, somewhat nostalgically, to the gradual disappearance of a strong and vibrant religious community and tradition that flourished in the village of Canterbury, New Hampshire, during the nineteenth century, near where Adams grew up as a child, while large-scale choral works such as El Niño (2000) and The Gospel According to the Other Mary (2013) cast a contemporary light on biblical texts.

Adams’s music often seems to belong to an ‘America of the moment’ – high octane journeys in fast cars and their subsequent valorisation and glamorisation in road movies. But there is also a very different America of the moment, one paralysed by fear and self-doubt.

Back in the mid-1960s, Reich’s early tape pieces It’s Gonna Rain (1965) and Come Out (1966) located America in a dystopian present, capturing the paranoia that gripped the country in the wake of the Cuban missile crisis in October 1962 (the ‘rain’ of a nuclear winter) or, in K. Robert Schwarz’s words, the ‘horrific racial strife that would soon engulf America’ during the race riots of the 1960s.

Later, the third act of Reich and Beryl Korot’s multi-media opera Three Tales (2002), entitled ‘Dolly’ also addressed contemporary issues relating to cloning and genetic engineering.

Steve Reich and Beryl Korot. Photo: Alice Arnold

Reich’s music also reflects an ‘America of the self’ and ties in with the composer’s quest during the late 1970s and 80s to look inwards in order to rediscover his own religious roots and identity. It resulted in a series of notable works, such as the rich, vibrant psalm settings of Tehillim (1982), and later on, the multi-layered multimedia opera The Cave (1993). In reality, The Cave is no more ‘religious’ than Adams’s Nixon in China is ‘political’, although both are informed respectively by religious and political themes.

Photos: John Adams, El Niño at the Théâtre du Châtelet, Paris (2000) © Kopie; John Adams, The Flowering Tree at Halle E+G, Vienna (2006) © Lisbeth Rojas; Steve Reich's Three Tales (2005) © Wonge Bergmann

The ‘America of the moment’ is linked to an ‘America of place’. Its cityscapes have served as inspiration for positive reflections, such as Reich’s New York Counterpoint (1985), in addition to more negative ones, such as City Life (1995) or Adams’s City Noir (2009). The rugged, wide open ‘frontier’ spaces of America’s Midwest and Southwest is celebrated in Adams’s Hoodoo Zephyr (1992–3) or The Dharma at Big Sur (2003), for example, while Reich’s ominous The Desert Music (1984), offers a harrowing glimpse of a world turned to dust following nuclear Armageddon. In all cases, a sense of place is animated by Adams and Reich’s keen sense of ‘psycho-geography’: these are not places captured in timeless isolation but conjured up through the composers’ own response to (and experience of) them.

Glass’s music captures the fragility and uncertainty of the American psyche, one that lies beneath the Gung-ho, machismo and hubris

Personal, spiritual and religious reflection relates to another kind of ‘America’: the ‘America of the mind.’ Glass’s music, in particular, captures the fragility and uncertainty of the American psyche, one that lies beneath the Gung-ho, machismo and hubris. The opening from his Glassworks suite (1982) presents a world that is both bittersweet and strangely familiar. Susan McClary sums it up: ‘before us glimmers once again the Romantic soul, decked out with all its requisite emotional trappings – alienation, memories of lost arcadia, and longing for utopia.’ It’s a grizzly paradox that Adams also tapped into in his autobiography Hallelujah Junction: ‘America loves its heroes [and] thrills at their triumphs … [but] we love even more to bear witness to their weaknesses, to see them fall from their pedestals, suffer humiliation, even degradation. In this way their eventual rehabilitations can be all the more bittersweet and inspirational for us. If they die before they are forgiven, we raise them up posthumously. It is part of the psychic drama, the dark, nether side of fame.’

Whether reflecting an America of the mind or the self, of a sense of place, a moment in time, or of the America of supermarket shelves and mass production, the music of Reich, Adams and Glass will forever resonate with the sounds that made – and changed – America during the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries.

Photo: Utah Desert © Deborah O'Grady

Listen to The Sounds that Changed America playlist on Spotify

Words by Pwyll ap Siôn

Pwyll ap Siôn is Professor of Music at Bangor University, Wales, and is the recipient of a Leverhulme Research Fellowship on the music of Steve Reich.

Illustrations by R N Taylor