It can be said that some legal practitioners might find it hard to approve the way the artists function. Don’t the artists bend the rules, challenge principles, hurt the feelings of the law-abiding citizens, and ridicule social standards?

Not just that. When it comes to the rules of artistic production, don’t the artists take the law into their own hands, change the goal posts at will, distort accepted values, and proudly boast about their (mis)conduct? On top of that, they may even claim reward for breaking taboos and demolishing aesthetic norms.

We know, of course, that such comparisons may be farfetched especially in a society like the UK. Sadly, though, it is not unusual for legal practitioners in many parts of the world to use similar arguments to ban artists from exercising their right to freedom of expression.

Artists are persecuted under censorship regulations imposed by repressive rulers, ideologies, political doctrines, or religious traditions. These practices ban artists from choosing at will either the forms in which they wish to express themselves, or what they wish to express, or both.

Where such impositions have been absent for a noticeable length of time, the arts have flourished, as have human rights, which is the field in which I am a practitioner. I find the flexibility and elasticity of the arts a great counterbalance to the rigidity of the laws and regulations.

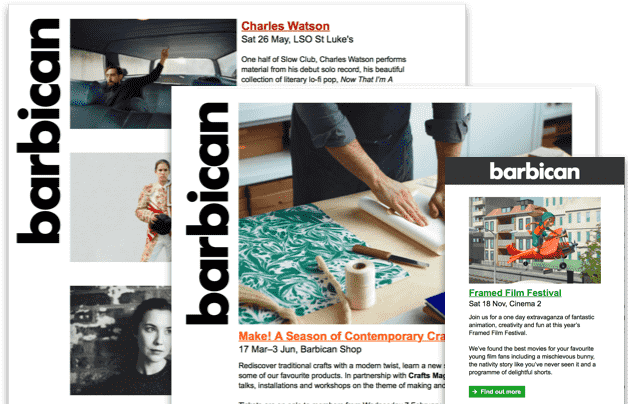

This urge is what took me to the Postwar Modern: New Art in Britain 1945-1965 exhibition at the Barbican. It was a boosting experience. A journey into the feelings and thoughts of the photographers, painters, and sculptors of the 20 year period the exhibition covers.